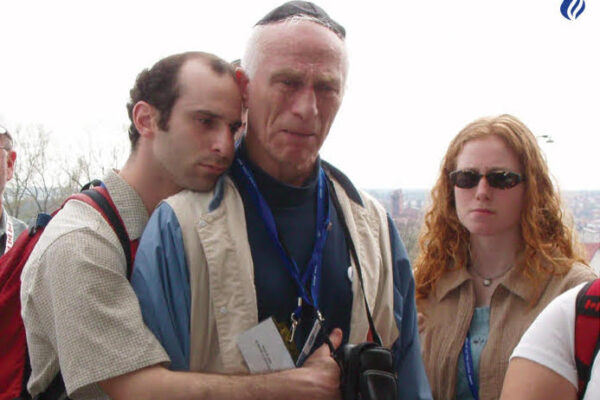

Barack Obama embraces Elie Wiesel as they visit the former Nazi camp at Buchenwald, Germany, in 2009. Wiesel never shied from using his political connections to promote lessons of the Holocaust, Catherine Porter writes. (MANDEL NGAN / AFP/GETTY IMAGES)

May Elie Wiesel rest in peace.

The Nobel Peace Prize winner who died last weekend at 87 was an incredible human being. Anyone who has read his switchblade of a book, Night, will know that.

Published in French in 1958, it was among the first Holocaust memoirs, recounting Wiesel’s time as a Nazi prisoner primarily in their murder capital, Auschwitz-Birkenau.

He arrived there in a crowded cattle car from Transylvania in the spring of 1944, just as the gas chambers were going into overtime, killing around 9,000 Jews a day, including his mother and youngest sister, Tzipora.

He describes arriving at night and seeing babies thrown into a burning pyre of little corpses.

He was 15, the age I was when I first read Night, and I thought he was incredible for purely surviving — in body and mind.

This past spring, I visited Auschwitz-Birkenau with the March of the Living. There, I got a deeper appreciation of just how remarkable Wiesel was — not just that he survived, but how he responded to it.

The two neighbouring camps built by the Nazis in southern Poland are now a state museum. A trip there is chilling for so many reasons, but I’ll just recount two. First, there is scale. When I followed the tracks into Birkenau, where Wiesel’s train unloaded, I gasped at the site of hundreds of chimneys in the fields around. They stretched on seemingly forever, over acres and acres. (The camp was in fact 171 hectares, just larger than High Park.) Each chimney had been part of a wooden barrack that housed up to 500 slave labourers — and they were the lucky minority not slated for immediate death.

Originally published HERE