Facing deportation to Auschwitz, 13-year-old Steven Fenves watched as neighbors in Hungarian-occupied Yugoslavia lined the stairs, “waiting to ransack whatever we left behind, cursing at us, yelling at us, spitting at us as we left.” Choking up, he also recalled in an oral history that the family’s cook rushed into the apartment to salvage artwork and a handwritten recipe collection, which she returned after the war.

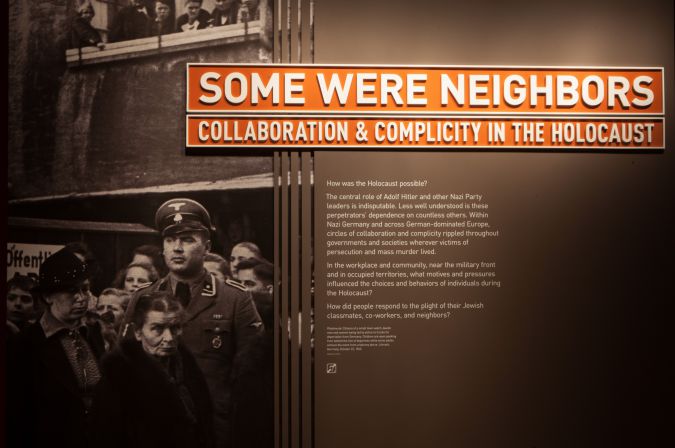

Such contrasting reactions to a crisis are a leitmotif of “Some Were Neighbors,” a provocative special exhibition at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, in Washington. The show, exploring complicity and collaboration in the Holocaust, regards the unfolding disaster less as an inevitable historical tragedy than as the sum of a series of choices. It opens with a quotation from the historian Raul Hilberg: “At crucial junctures, every individual makes decisions and… every decision is individual.”

It remains difficult to determine why some people risked their lives to save acquaintances or even complete strangers while others abandoned or betrayed neighbors and friends. Political circumstances varied; so did character. The historian needs to take account of morality, psychology, sociology and economics, and even so, answers may remain elusive.

The exhibition is filled, perhaps to a fault, with questions. Its images and labels interrogate the actions — and inaction — of bystanders and accessories to the ostracism, deportation and mass murder of Jews (and other targeted groups) in Nazi Germany and across Europe. The focus isn’t on the most notorious perpetrators, but on lesser villains, fellow travelers, compliant bureaucrats, those who might have acted and didn’t. The heroism, or simple refusals, of the few throws the dismal complicity of the many into sharper relief.

Visitors are asked to ponder who exactly was culpable. Did the mere use of swimming pools and other amenities forbidden to Jews make Germans complicit in discrimination? How should we assess the residents of a German town who, in 1941, watched the ritual humiliation of an “interracial” couple, a German man and a Polish woman? What about the bureaucrats who created maps, registration lists and ID cards that helped the Nazis isolate and kill Jews? Or the editor of a travel guide to German-occupied Poland who omitted any reference to Jewish sites?

Greed, fear, social conformity, the desire for power and revenge, as well as Nazi ideology and resurgent nationalism, all played a role in spurring collaboration. But the admixture varied, and individual motives are not always ascertainable. “Get with the times!” one man shouted at a policeman guarding a Jewish family during the 1938 Kristallnacht pogrom — as though anti-Semitic violence were merely the latest fashion. Many images underline the power of economic motives: stacks of confiscated Jewish furniture, crowds looting Jewish stores or clamoring to bid on stolen goods.

But vitrines also display gold jewelry, silver candelabra, religious books and other items — including that Fenves family recipe collection — saved by neighbors and friends.

The exhibition’s most powerful technique is encouraging visitors to look more deeply and critically at familiar images. Photographs of Jews being rounded up are annotated, with labels identifying not just Gestapo agents and other police, but also ordinary citizens staring from sidewalks or apartment windows. A chilling silent film from Latvia pictures German sailors in bathing suits watching as members of an SS killing squad, aided by Lithuanian collaborators, shoot Jews who tumble into pre-dug graves.

Contrasts are emphasized: Amateur film footage from Kristallnacht depicts firemen hosing down a building while a synagogue burns. But we also learn that the mayor of Fischbach successfully discouraged the torching of a synagogue, declaring, “We are not arsonists.” Many Jews recounted being shunned by onetime friends. But Hannah Altbuch recalled that, after Kristallnacht, she and other Jewish classmates returned to school to find their desks filled with fruit and candy.

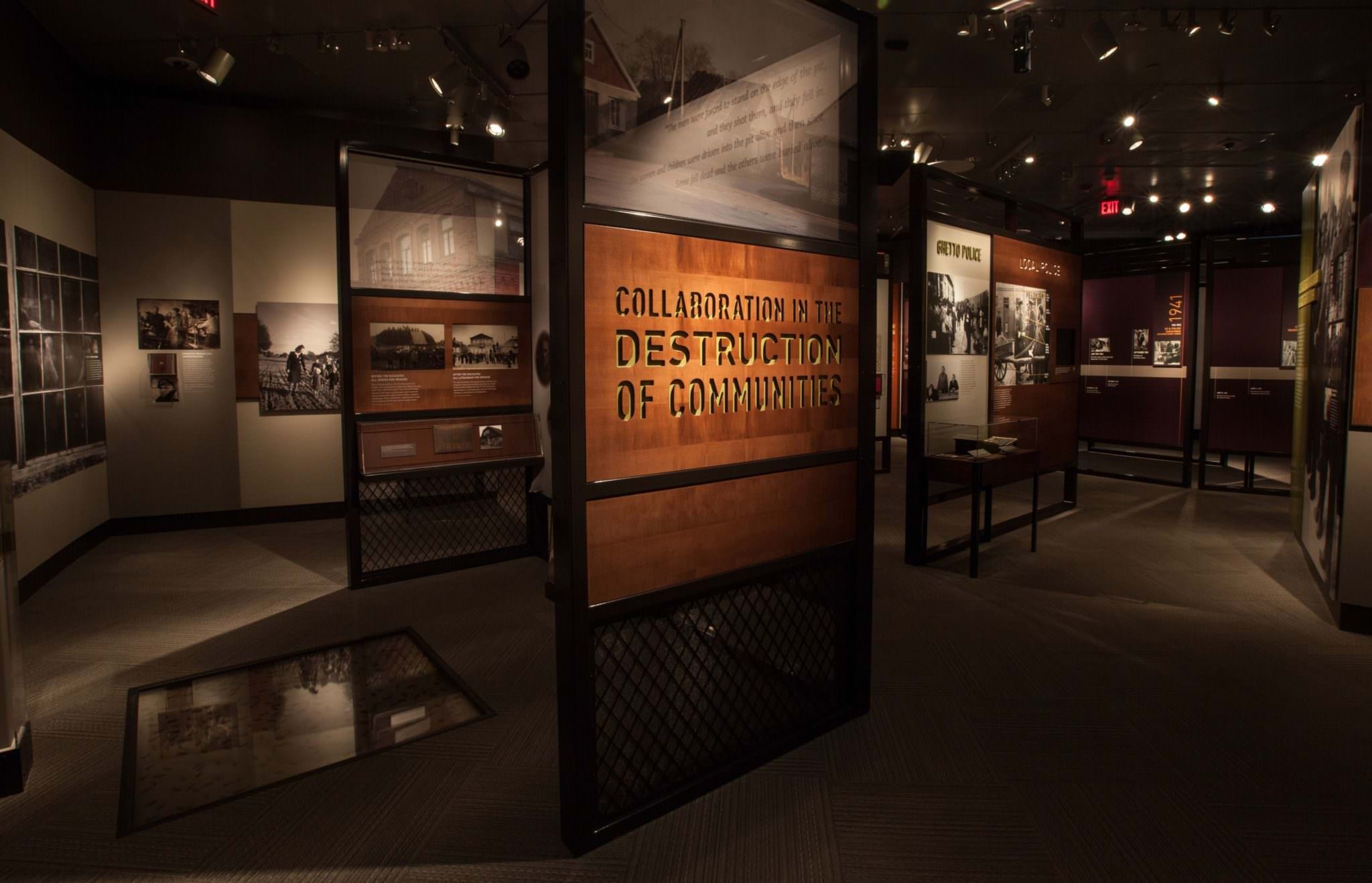

“Some Were Neighbors” is an ambitious, sometimes overwhelming show. Beginning with a hallway of prewar photographs of Jews and non-Jews working and socializing together, it encompasses the rise of Nazism, the conquest of Europe, and the spectrum of reactions and consequences. Its organization is at once chronological, geographical and loosely thematic, with topics such as “Complicity in Exclusion” and “Complicity in Acts of Public Terror.” Its mazelike design that can be confusing.

At its heart are the filmed testimonies of survivors, witnesses and collaborators. One Lithuanian army volunteer talks of shooting a middle-aged Jewish man in Belarus and attending a Catholic Church with his unit to participate in group confession. In the online version of the exhibition, another Lithuanian guard recalls that a young woman he had danced with in high school hugged him and begged for her life. “It was terrible,” he says, but, ringed by the Gestapo, “there was nothing you [could] do.”

The grimness of these testimonies is offset by a few profiles in courage — of civil servants, farmers and others who dared to transgress regulations and defy occupying armies. The exhibition also points out that, under wartime stresses, even stories of rescue could turn morally ambiguous, with rescuers threatening to oust those in hiding, or compelling them to work without pay.

Amid a welter of words and images, a few linger. Like the memories of Manfred Wildmann, a printer’s son from Philippsburg, Germany, who described residents gathering to observe the deportation of the town’s Jews. A single woman emerged from the crowd to embrace his mother. “Nothing happened to her,” he recalled. “If more people had done something like that, things may have changed.”

“Some Were Neighbors: Collaboration & Complicity in the Holocaust” runs at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, in Washington, D.C., through 2017.

Originally published HERE