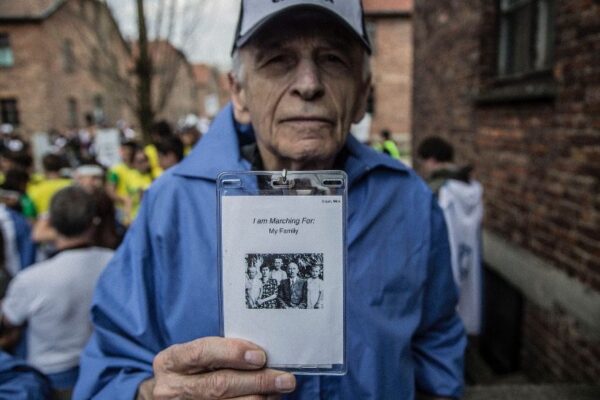

Holocaust survivor Vivianne Spiegel with her only picture of her parents, who were both killed at Auschwitz. Photo: Wayne Taylor

As she has done for so long, Vivianne Spiegel searches the fading photographs for her parents’ faces among the piles of bodies.

She was seven years old when she saw her mother, Tauba, for the last time. It was Paris, July 1942. Her father, Moshe, a Polish shoemaker, had already been captured and turned over to the Nazis.

He was among the first prisoners delivered to the concentration camp where history’s largest genocide in one location would take place.

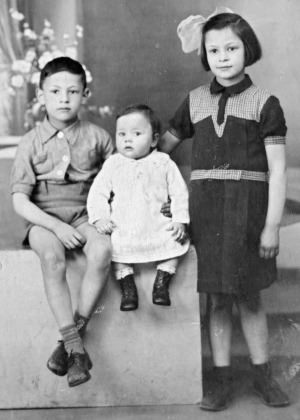

Vivianne Spiegel (right) with her two younger siblings, Albert and Regine. This photo was given to their father when he was at an interment in Pithiviers, France. His family hope he had it with him when he was deported to Auschwitz. Photo: Wayne Taylor

AdvertisementThey suffered in hot, cramped conditions with no food or water. Most were sent to transit camps, then herded onto cattle trains destined for the gas chambers at Auschwitz.

In a lifesaving turn of fate, Tauba and her three children were released after appealing to a sympathetic French policeman.

The railway tracks at the former Nazi concentration camp Auschwitz-Birkenau in Oswiecim, Poland.

Not long after the train pulled out, Tauba was denounced. Years later Vivianne would learn how her mother ran up the stairs of their building when the police came for her. Tauba was finally captured on the roof.

This is the last thing Vivianne knows about what happened to her mother, except that she, too, was murdered at Auschwitz.

“We never saw her again,” Vivianne says. “She knew what was going to happen, but we didn’t know and she certainly didn’t tell us. She told me that we were only going to the countryside for a short while.”

Survivors of Auschwitz shortly after the concentration camp’s liberation in 1945.

This week marks the anniversary of Auschwitz’s liberation in 1945. It has been more than seven decades since the last of the men, women and their children arrived at Death Gate, were divided into groups and either sent to work or to the grave.

Tauba and Moshe were among more than 1.1 million people who perished at the Nazi concentration camp that stretched to the horizon, spanning a terrifying 40 square kilometres.

Mostly they were Jews, but Poles, Gypsies, Soviet prisoners of war, gay and disabled people were also targeted.

Vivianne doesn’t know if her parents were reunited behind the barbed wire fences before they died. She hopes they were. They are together now, in the frame she keeps on the dressing table in her Caulfield North home. The black and white photograph of each of her parents, taken from their identification papers, is all she has left of them.

The only photographs Vivianne Spiegel has of her parents, Moshe and Tauba. Photo: Wayne Taylor

In 2010, Vivianne and her two sons retraced her childhood in France and travelled to Auschwitz for the annual March of the Living. They walked three kilometres from Camp Number One to Birkenau in tribute to her parents.

“It was a nightmarish experience for me, but it was also a form of closure,” she says. “I’ll never go again. It’s too horrible.”

Born Berthe, she changed her name to Vivianne – meaning life or alive – after coming to Melbourne. She feels her mother gave her a second life when she put her on the train out of Paris.

But for 40 years Vivianne didn’t utter a word about her parents. Not even to the family who adopted three orphans of the Holocaust shipped to Australia after the war.

The main gate of the Nazi Auschwitz death camp at sunrise. Photo: Janek Skarzynski

Now 81, the grandmother shares her story at the Jewish Holocaust Museum in Elsternwick. She speaks about her fear of death and of the recurring nightmares. But she is haunted most by photos of the massed bodies.

“At first I couldn’t look, but slowly I acquired the strength. And then I started looking for their faces,” Vivianne says. “When I think of them on top of the piles of corpses it sends shivers down my spine.

“But I still look for them when I see new footage. It’s something I’ve always done. I’ve never found them.”

Originally published HERE.