For my father, a strong Israel as the home of the Jewish people was the only answer to the lessons of Kristallnacht.

Prof. Steinberg is taking part in March of the Living “Let There Be Light” global initiative in commemoration of “Kristallnacht”

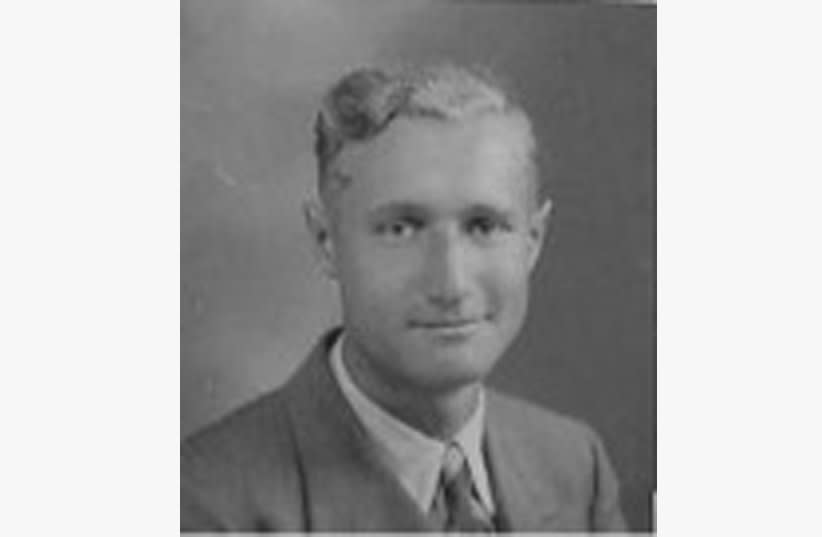

My father, Henry Steinberg, was born in Berlin – one of eight children, four brothers and four sisters. Anne (Fuhs) Steinberg, my mother was from Halle, in what became East Germany. They both went from Germany to England through the Kindertransport, met in London and were married in 1948. My mother’s parents and brother made it to Shanghai during the war, and afterwards, to California. After I was born, we joined them. My parents were very involved in the Jewish community and in support for Israel, where his father and one of his brothers lived. His four sisters and mother were murdered by the Nazis.

My mother was 11 when the Kristallnacht pogrom took place. Apparently where she was, the impact was not felt, and she went to school as usual the next day. In her autobiography, she wrote “As I entered the classroom, the teacher sent me home right away as from that day on Jewish children were not allowed to attend German schools any longer. That was the end of my education in Germany.”

My father was 15, living and Berlin, and witnessed the Nazi rampage directly. In his autobiography, he wrote: “If anybody has the notion that most Germans were not Nazis, the Kristallnacht dispelled that myth for me and everybody else who witnessed it. In November 1938 I was 15-3/4 years old. I saw the crazed Germans. Like a raging mob, they were insatiable. They just kept going, from street to street, from synagogue to synagogue. Smashing, looting, and burning. The next day they made Jews clean up the mess. All I could think of while watching this was that they will pay for this.” With his older brother and others, he ran to the local shuls (small synagogues) to save the Torah scrolls, shofars, and other ritual objects from destruction. He carried the shofar in his backpack to England a year later, and blew it every year on Rosh Hashana in our California synagogues until he was 80.

My father had a basically optimistic personality, despite everything and like many others, my parents put Nazi Germany and the Shoah largely behind them, to the extent possible, making new lives for themselves and for us, as children. But when there antisemitic incidents, he would remind us about what the Nazis did and of his memories of Kristallnacht in particular. In our house, long after the war, we did not buy German products – the memories were imprinted on all of us. For my father, a strong Israel as the home of the Jewish people was the only answer to the lessons of Kristallnacht.

My father thought that the world did not learn the lessons of the Shoah and even worse, many Germans and the descendants of their European collaborators, formed their own distorted versions of the Nazi era. His message for the younger generation was to be strong, be proudly Jewish and fight for what is right.