As scholars mark first German edition since 1944, Jewish community leaders unconvinced by idea of teaching Hitler’s manifesto ‘as a vaccine against extremism’

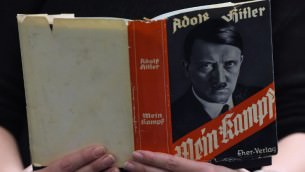

As Adolf Hitler’s last official residence, the German state of Bavaria has kept the copyright of the genocidal dictator’s “Mein Kampf” under lock and key since the end of World War II. Forced into the role of a taboo’s reluctant guardian and although most historians see it as an important source on the Nazi period, for 70 years the state has prohibited publication of Hitler’s monstrous autobiographic manifesto of anti-Semitic ideology. That copyright expired on December 31, 2015.

Hitting the shelves in Germany on January 8, the Munich-based Institute for Contemporary History’s re-published “Mein Kampf” is a heavily annotated edition with commentary almost as long as the 800-page original text. Work on the annotated version took three years and for the research community, this new two-volume edition is an opportunity to finally fill a major gap.

While both sides of the controversial public debate wonder about the efficacy — and need — of republishing Hitler’s lengthy screed, many don’t realize that, alongside other excerpted texts of Nazi propaganda, “Mein Kampf” is already included in standard German history textbooks.

When the ICH presented the project to an international commission of researchers, it has garnered approval from historians including Dan Michman, head of the International Institute for Holocaust Research at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. At the hefty sum of 59 Euros ($65), the new edition is not likely to become a bestseller. But as the first print publication of “Mein Kampf” in Germany since 1944, it has set off heated discussion in both domestic and international forums.

Upon the book’s publication Friday, World Jewish Congress President Ronald S. Lauder released a statement condemning the scholarly endeavor. “It would be best to leave ‘Mein Kampf’ where it belongs: the poison cabinet of history… This project may be well-intended, but the Bavarian government was right not to allow its republication until the expiry of the copyright, or to support a new edition financially,” says Lauder.

Head of the Institute for Contemporary History Andreas Wirsching says, however, publishing the scholarly edition promotes responsible research and counters unannotated versions that Germans can easily buy online through international booksellers. The annotated edition “contributes to the urgently needed demystification of this crucial Nazi-era text,” says Wirsching.

Indeed, most scholars agree it’s high time “Mein Kampf” be stripped of its mystical aura, and that continued censorship is counterproductive to that goal.

“What can’t be examined, can’t be discussed – it is mystified instead,” writes Christoph Schwennicke, the editor-in-chief of the German political monthly “Cicero” in a recent article. He calls for an open examination of its content, and wonders whether its publication is not long overdue.

“Isn’t it relevant to know the train of thought that fed the German catastrophe?” he writes.

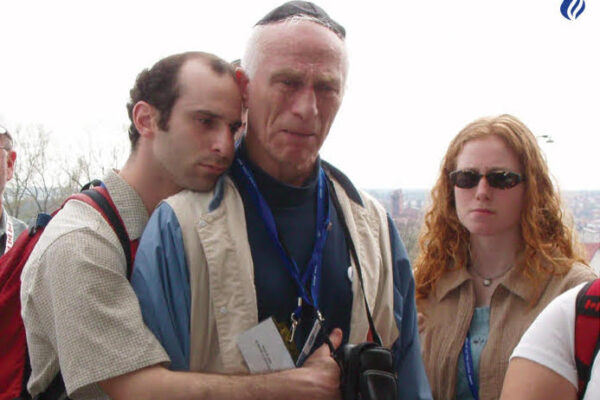

Head of the Institute for Contemporary History Andreas Wirsching (Institut für Zeitgeschichte München)

Even the leader of Germany’s Jewish community, Joseph Schuster, has agreed that the book can contribute to a greater understanding of the Nazi era and the Holocaust and is in favor an annotated edition.

But now that it can theoretically be published freely, Schuster emphatically warns against uncontrolled circulation of unannotated “Mein Kampf” editions. He has called on the German state’s institutions to do all they can to prevent its sale and distribution.

This public call against unannotated distribution does not go far enough for Charlotte Knobloch, head of Munich’s Jewish community and commissioner for Holocaust memory at the World Jewish Congress.

In a recent conversation, Knobloch told The Times of Israel that selling “Mein Kampf” in Germany in any form is a slap in the face to Holocaust survivors’ associations worldwide that, she says, can’t grasp that the book will be again legally available in Germany.

“The fact is, just dealing with the book raises interest in it – and that interest, for many, is not in the commentary but in the original text,” says Knobloch, who fears the annotated editions won’t hit their mark.

Charlotte Knobloch, head of Munich’s Jewish community and commissioner for Holocaust memory at the World Jewish Congress (courtesy)

At the moment, it looks as though the annotated edition of “Mein Kampf” is still likely to be the only one on sale in German bookstores. German justice officials have announced that anyone who publishes the book without proper commentary will be prosecuted for inciting racial hatred, under the unique law which allows Germany’s democracy to defend itself against anti-democratic forces.

However, taking a clear stance on the question of how the book should be handled in schools, Knobloch also vehemently opposes covering “Mein Kampf” in the classroom.

“There’s generally too little time in class to deal with National-Socialism, the Holocaust and the Second World War in a substantial way. It doesn’t make sense to spend the little time there is reading hate speech,” she says.

Orthodox Berlin-based Rabbi Yehuda Teichtal echoes those fears, saying that the risk of introducing it into schools is greater than the “doubtful benefit of teaching it as a vaccine against extremism.”

But German education representatives disagree and those supporting discussion of excerpts of “Mein Kampf” in schools include German education minister Johanna Wanka, of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s CDU party. Now that it’s such a hot topic in the media, Wanka says, students will have questions concerning the book. It needs to be talked about in classrooms, she told a Bavarian newspaper.

The longtime president of Germany’s teacher’s association Josef Kraus agrees, saying rather than students secretly buying the book online, it is better to turn it into a topic of classroom discussion, where history or politics teachers have a chance of influencing them.

But German education representatives disagree and those supporting discussion of excerpts of “Mein Kampf” in schools include German education minister Johanna Wanka, of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s CDU party. Now that it’s such a hot topic in the media, Wanka says, students will have questions concerning the book. It needs to be talked about in classrooms, she told a Bavarian newspaper.

The longtime president of Germany’s teacher’s association Josef Kraus agrees, saying rather than students secretly buying the book online, it is better to turn it into a topic of classroom discussion, where history or politics teachers have a chance of influencing them.

“No one voluntarily tortures himself through Hitler’s ‘Mein Kampf.’ It’s too badly written for that,” prominent Green party politician Volker Beck, head of the important German-Israeli parliamentary group, told the German daily Handelsblatt.

“No one voluntarily tortures himself through Hitler’s ‘Mein Kampf.’ It’s too badly written for that,” prominent Green party politician Volker Beck, head of the important German-Israeli parliamentary group, told the German daily Handelsblatt.

And perhaps there are better texts to address anti-Semitism and Nazi ideology. “The book is confusing and bulky, and therefore hard to apply in class,” says Ulrich Bongertmann of the Association of German History Teachers. He names the 1920 Nazi party platform or the Nazis’ own school propaganda texts as more suitable alternatives.

Interestingly, Nazi era texts are already utilized in other school subjects, such as German language studies. Since it is part of the state curriculum for German high school majors to identify “rhetorical strategies that are used to influence readers or listeners,” Joseph Goebbels’s Sportpalace speech and other Nazi diatribe are used to discuss oratorical devices and look at differences between news and propaganda, and demagogical and charismatic leadership.

This use of Nazi texts, including “Mein Kampf,” has already caused pushback from students. In a recent newspaper oped, 16-year-old high school student Noah Gottschalk harshly criticized the idea of using “Mein Kampf” in German lessons.

In his article “Hitler instead of Schiller?” he opines that from a literary and stylistic perspective, Hitler’s hate manifesto belongs in the trash and does not deserve to be taught next to the great names of German literature.

In his article “Hitler instead of Schiller?” he opines that from a literary and stylistic perspective, Hitler’s hate manifesto belongs in the trash and does not deserve to be taught next to the great names of German literature.

And as a writer for the conservative German daily Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung pointed out, it would actually be an ironic twist of history to make “Mein Kampf” required reading at schools. It would be giving it merit it did not even receive in Hitler’s own time. Although the book was widely read in schools during the Nazi period, it was never a mandatory part of the curriculum.

By Miriam Dagan