The flax-retting area at Unterschleissheim, as it looked during the Holocaust. (Peter Vahlensieck)

In 2000, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, tasked researchers with creating a comprehensive, single-source record that would accurately document the thousands of persecution sites the Nazis had established. The USHMM estimated that the team would uncover about 5,000 persecution sites, which would include forced labor camps, military brothels, ghettos, POW camps, and concentration camps.

But as the research got underway that number skyrocketed.

In 2001, the number had doubled. A few years after that, researchers had already discovered 20,000 sites. Now, the “Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933-1945” contains more than 42,500 sites that the Nazis used to persecute, exploit, and murder their victims.

In 2001, the number had doubled. A few years after that, researchers had already discovered 20,000 sites. Now, the “Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933-1945” contains more than 42,500 sites that the Nazis used to persecute, exploit, and murder their victims.

“You could not turn a corner in Germany [during the war]… without finding someone there against their will,” said Megargee, speaking ahead of Friday’s International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Cover of a volume of the ‘Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933-1945’ (courtesy)

For Megargee, counting the sites was one of the main challenges of the project. For example, there were camps that changed purposes over time and brothels that existed within camps. To err on the side of caution, sites like these were counted only once. Researchers also refrained from counting sub-camps, of which there were tens of thousands.

For researchers to conclude that a site had existed, they could not just rely on one person’s testimony. It was imperative that multiple witness testimonies and official documents corroborated each other in order for a site to make the series.

Because a gap of more than half a century existed between when the last camp was liberated and when the project began, one can only imagine how many sites will remain forever unrecorded. Not only were records and testimonies destroyed or lost during and after the war, they were also in a myriad of languages, or hidden by embarrassed, indifferent or unapologetic parties. Some were taken to graves by witnesses and victims who had died before the new millennium.

Still, the number of persecution sites discovered was more than eight times that which experts at the USHMM — the vanguard for Holocaust research — had predicted.

Perhaps, however, it was only possible to reach this shocking figure precisely because of the passage of time — for time brought to the project an element that nobody had foretold.

Skeletons in the closet

When Hermann F. Weiss decided to dig into his family’s past in 2001, his siblings had disapproved. His brother told him that there was already enough written about the Holocaust. Weiss disagreed.

“My family was anxious,” Weiss admitted. “They were afraid I would discover things about my father that were terrible.”

His father, whom Weiss describes as an “accomplice,” was an engineer overseeing the construction of infrastructure for Schmidding, a German missile development company. Weiss needed answers. His father’s role during the war had haunted him.

Weiss had even moved to the United States partly as a way to escape this familial and national burden, but the weight crossed the Atlantic with him. He felt depressed and ashamed. The only thing that Weiss saw as a reasonable response was “to give voice to the many unknown [victims].”

He focused his research on Silesia, a region that spans parts of Poland, Germany, and what is today the Czech Republic. Silesia was where his father had worked for Schmidding and it was where, in 1944, Weiss had spent the seven happiest months of his childhood because “there was no bombing.”

But investigating the atrocities in Silesia seemed to have no starting point. “Most historians do not touch [these sites],” he said, “because there are too few war-time documents.”

After pouring through this limited number of documents and survivor memoirs, Weiss frequently turned to a practice despised by those forced to use it: cold calling. For example, he had read a memoir about a forced labor camp in Silesia that accused a commander named Kurt Pompe of barbaric acts. Weiss had learned that the first name of Pompe’s youngest son was Herbert. He found six Herbert Pompes in the German online phone directory, and his second call was answered by Kurt Pompe’s daughter-in-law.

The conversation revealed a number of things, including where and when Kurt Pompe had died. This fact allowed Weiss to uncover Pompe’s denazification file, which showed that the Americans had been unaware of Pompe’s crimes. Weiss set the record straight in a Yad Vashem publication, and, in much briefer terms, in encyclopedia entries for camps where Pompe had committed his crimes.

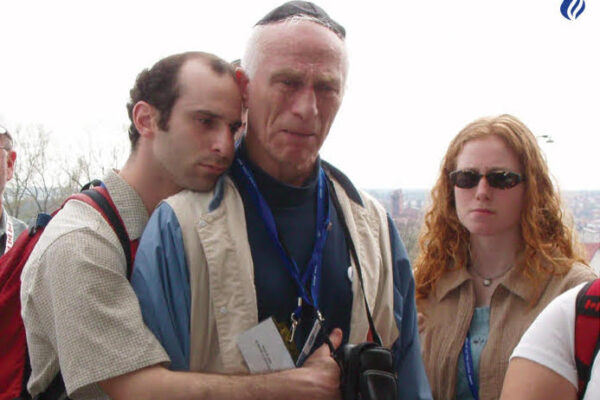

Hermann Weiss went back and investigated the crimes committed in his hometown growing up. (Courtesy)

“The encyclopedia entries have to be very condensed,” Weiss explained, a hint of regret in his voice.

Weiss’s research helped him to produce about two dozen entries on forced labor camps in Silesia for the encyclopedia series. Prior to his digging, most sites had little information published about them. Six sites, in fact, had never been written about before and were Weiss’s very own discoveries.

And yet some of Weiss’s most indelible memories from his research have no place in the encyclopedia.

For instance, on a trip to Silesia, Hermann Weiss discovered one undocumented persecution site that appeared as it would have days after the arrival of Soviet troops. Villager testimonies allowed Weiss to locate six unmarked graves, where three Poles and three Jews who had been murdered were buried. Four of the six mounds were still visible. There was no space in the encyclopedia to tell these stories. But like the specter of his father’s work, it was these stories that gnawed at him.

“The seeming insignificance of it,” Weiss explained, “was so significant.”

Dining with a murderer

Katherina von Kellenbach had grown up referring to Alfred Ebner as her uncle. Yet when the family got together with Ebner after World War II, his presence at the table never sat quite right with von Kellenbach.

Ebner had been responsible for setting up, running, and orchestrating the mass killings of more than 20,000 Jews in Pinsk, where 86% of ghetto residents were women and children. After the war, when the courts pursued top Nazis, Ebner was granted clemency, having been diagnosed with a form of dementia.

But at the family table, he seemed perfectly fine to von Kellenbach. In fact, the other family members had viewed Ebner as the victim. They considered that it was Ebner who had suffered because of these so-called unfounded accusations.

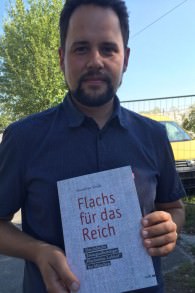

Researcher Max Strnand at a persecution site with the book he authored. (Noah Lederman/Times of Israel)

If the courts would not hold Ebner accountable and if Belarus had no public memory of these atrocities, von Kellenbach decided that she would investigate.

In 1999, she began her inquiry into her uncle’s past, visiting the Yad Vashem archive to gather data on Pinsk. But many documents were in Hebrew or other languages foreign to her. She needed help making sense of things. When she learned of a survivor from Pinsk who could be of assistance, she hesitated.

“It was hard to call up some survivor and say ‘I’m the niece of Alfred Ebner,’” she said. But that’s just what she did, and for two days she and survivor Nahum Boneh sat at his kitchen table with all of the documents, unpacking Ebner’s crimes.

For years, von Kellenbach worked to rescue documents trapped in other countries’ archives and at times had to run a cloak-and-dagger research operation. Since authorities would never have allowed her to conduct an unfettered investigation on a well-known perpetrator from the Pinsk region, she pretended to research partisans stationed in the vicinity of Pinsk. This gave her access.

Her family cast a hostile eye on her work. But the research whittled at the lies, and Ebner’s credibility in the family weakened. For the most part, everyone stopped protesting her efforts, though Ebner’s children continued to view their father “as a good man, who helped many people,” said von Kellenbach.

During one session with the documents, von Kellenbach had discovered writings in which a police officer under her uncle’s command complained about not knowing whether he should kill the child before the mother, or vice versa. On the day in question, Ebner had orchestrated the murders of more than 7,000 people.

“There’s no way you walk out [from the archive] at 5:00 p.m. as a human being,” von Kellenbach said after reading those documents.

Time is on our side

The researchers are far more diverse than the relatives of perpetrators and accomplices. While the project has many dyed-in-the-wool historians on board, there are researchers who survived one or more of the 42,500 sites, as well as the descendants of survivors.

Hannah Fischthal, for example, researched sites where her uncles had been imprisoned. Her work has helped to debunk inaccuracies. Karwin is a camp where her uncle had been imprisoned. It had always been considered a POW camp because of how it was characterized in a documentary film about an Italian prisoner. But Fischthal proved that Karwin was, in fact, a predominantly Jewish camp. The record was corrected and the Jewish victims were recently honored with a plaque at the site.

Some researchers are finding camps in the way paleontologists might dig up dinosaurs. Now that the technology is available, forensic archaeologist Caroline Sturdy Colls has conducted ground-penetrating radar research near Adampol, where she has uncovered buried evidence that corroborated witness testimony and yielded new finds.

A factory in Unterschleissheim, built on the location where Jewish and other slave laborers worked with flax during the Holocaust. (Noah Lederman/Times of Israel)

Martin Dean, who worked as the series editor on the encyclopedia before leaving the museum and the project at the end of 2016, had originally been employed as a war crimes investigator with Scotland Yard. Dean had spent years building cases against perpetrators, but most yielded inadequate results — some former Nazis were excused because of poor health, others died before being brought to trial.

While Dean’s expertise as an investigator was restricted by the courts, his acquired knowledge helped to correct the record for numerous previously unknown persecution sites, including some of the 300 ghettos that had never been documented before this project.

Bunker buster

About 14 kilometers (eight miles) north of Munich, is the town of Unterschleissheim. The entire area was once a persecution site, and researcher Max Strnand helped to document the Lohhof flax-retting plant, the camp that had once occupied these grounds.

Besides the camp, Strnand explained, there was hardly anything in Unterschleissheim during the war. The location then only had a train line, a warehouse, and a tower, all of which still exist today: the train station is just down the road from where the warehouse and tower — now swathed in modern day advertisements — sit inside a locked compound.

Because the land had been empty, the Nazis brought Jewish slaves and POWs to the fields to lay and dry out flax. The fibers from the stalk were then brought to the warehouse, where they would be stored as raw materials for linens.

Before Strnand, there was no single source that told the story of the camp in Unterschleissheim and facts were scattered about like confetti after a hurricane. But Strnand patiently unearthed an entire history, including information about the prisoners, of which there were typically 200 at any one time.

“We don’t know if people were executed here, but there were many accidents,” Strnand said. He noted, however, that only 10% of Jewish prisoners who came through Unterschleissheim survived the war, as the Jews from this camp were usually sent directly to extermination camps like Treblinka or Sobibor.

“This topic is something that concerns everyone who lives here,” Strnand said, who now sees his book about Lohhof implemented into local schools’ history lessons. Prior to his book’s publication, most people in town had never known that a camp had existed.

According to the city’s Head of Culture, Daniela Benker, there are plans to build a memorial site by 2018. But since the structures belonging to the former camp are behind a gate on private land, the aim is to build a memorial elsewhere — perhaps at the train station down the road — where it can be visible to the public.

While Strnand walked the site, a truck approached the compound and the gate opened. He followed the truck inside and found a hulking electrician ending his day. Strnand introduced himself and asked permission to walk the grounds. The electrician pulled out a key that accessed a supply shed, a former Nazi bunker.

This electrician’s shed in Unterschleissheim was once a Nazi bunker. (Noah Lederman/Times of Israel)

The bunker looked like a typical storage shed; however, the reinforced roof that once provided additional safety against a bombing was still visible. What was most shocking was Strnand’s surprise. The researcher, who knew more about the camp than anyone else, was seeing the insides of this building for the very first time. Even the experts were still uncovering new facts about the hidden stories of the Holocaust.

The work is never done

The truth is much will remain unknown about the victims or the places that the Nazis used to dehumanize people and commit murder. But the encyclopedia series is the largest effort to most thoroughly document as many sites and include as much testimony as possible. When it is completed in 2025, many of the project’s researchers will still continue their work.

After Hermann Weiss finished correcting the record on Kurt Pompe, the Nazi from Silesia, he looked into the records of other criminals never brought to justice. Weiss came across hundreds of testimonies about a man named Hauschild, one of the most sadistic perpetrators in the Silesia region. Despite the accounts and accusations against Hauschild, the man remains Weiss’s greatest puzzle. Weiss cannot connect him to any particular Nazi organization and thus cannot condemn the man or his record accurately.

“I keep collecting. I keep looking,” Weiss said. “This is an example of how so many things about the Holocaust might be unknown forever… [The encyclopedia] will provide some basis for further work.”

Originally published HERE