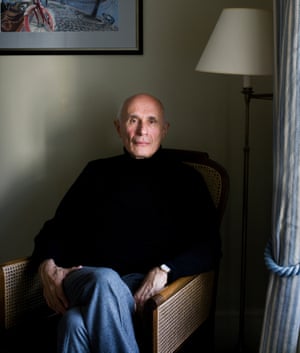

Arno Roland in New Jersey, one of more than 100 Holocaust survivors photographed by Harry Borden over the past five years.

Among the horrors that Primo Levi quietly and even matter-of-factly documents in If This Is A Man – that greatest of all accounts of incarceration in a Nazi death camp – is a dream of invisibility. Not invisibility in the here-and-now of camp life, which might have been welcomed, but invisibility in the longed-for future, back home “among friendly people”. It is an as-though invisibility, not an actual one. Yes, they see him, but they cannot hear him. When he speaks of where he’s been, his listeners don’t follow. Don’t or won’t? This distinction is not made and perhaps cannot be made. Quite simply, his words don’t reach them. “They are completely indifferent; they speak confusedly of other things among themselves, as if I was not there. My sister looks at me, gets up and goes away without a word.”

On waking from this dream, Primo Levi experiences a “desolating grief”. But he is not the only prisoner to have dreamed this; others anticipate the same anguish of the “unlistened-to story”. Perhaps because they can barely trust the witness of their own eyes, they know how hard it will be for others to believe – to allow themselves to believe – the stories they have to tell. Better not to know.

Later in the book, Levi describes the gleeful malice with which a German guard confirms what these dreams presage. Don’t hope to be heeded when you return home, he warns. The words you speak will be as voices to the wind. The future will be deaf to you. History will expunge your experience as completely as it will expunge our guilt.

Many years have passed since the first publication of Levi’s great work and we might speculate that things are simultaneously better and worse than he feared. We are familiar with stories of survivor silence – the decades of speaking not a syllable, of not wanting to put back into words what had now retreated, for safety’s sake, into nightmare, decades of fearing being invisible and disbelieved, perhaps of wanting to be invisible and disbelieved, as though that might make the memory of the experience vanish. We know, too, that such traumas don’t stop with the generation that went through the camps, but are passed on to children and even grandchildren in a terrible inheritance of guilt and shame. There are instances of too much memory, not too little, where the necessity to keep on telling, or at least to keep on remembering, becomes an intolerable burden.

But however oppressive that burden, however cruel the cost of remembering – “If you could lick my heart, it would poison you,” a survivor of the Warsaw ghetto famously admitted – the story has to go on being told. Not only as an individual imperative, but as a communal duty. Because for all the apparent “visibility” of the Holocaust today – and the memorials and museums and films and books and articles on the subject certainly seem to have given the lie to the prison guard’s hellish prognostications – there remain voices urging scepticism, forgetfulness, even a renegotiation of pity. “Negators of truth”, Levi called them.

Literal negators of the sort who once crawled over what was left of the camps with tape measures and set squares to prove the gassings were exaggerated or even impossible – the foot soldiers of denial – enjoy less credence than once they did, except in some Middle Eastern countries where antisemitism grows fat on conspiracy theory: Iran, for example, which sponsors an annual Holocaust cartoon contest, lampooning Jews and their fabrications. Elsewhere, Holocaust denial takes subtler and more insidious forms, now as Holocaust fatigue, in the course of which victims become confused with perpetrators, or dismissed as participants in mere “white-on-white crime”, warranting neither pity nor recognition; now as Holocaust avidity – a species of competitiveness whose aim is to wrest the Holocaust from the Jews who, in this narrative, are presented as greedily insisting on an exclusivity of suffering.

There are fewer and fewer survivors left to speak about what only they can know. It is all the more important, then, that they bear witness to a truth that so many do not want to hear. Not sentimentally, or morbidly, not with self-pity or in expectation of praise or admiration, but with the strength of certainty. After a while there is nothing left you have to prove. There you stand, and your resolution is your truth; let the malicious and the jealous of heart deny you as they will.

In his wonderful photographs, Harry Borden offers to our gaze precisely that resolution. His subjects have experienced the worst and seem now not to be afraid of anything more the world can say or do to them. The nobility of these photographs resides in the something undefinable Borden sees, and the unblinking steadiness with which he sees it – call it an indomitability of spirit, neither bitter nor disillusioned, ferocious nor reconciled. In the face of so much to be appalled by, his subjects give a degree of hope, if only by the quiet, unanswerable quality of their endurance. Not a hope that such events will never be repeated, or even that they will ever be fully understood, but that a still, small determination to look horror in the face and speak the truth survives beyond the desolation of grief.

Survivors’ stories: Peter Lantos

Peter Lantos was born in Hungary in 1939. Aged five, he was sent with his parents to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in Germany. He has lived in the UK since 1968.

I was at Belsen in the winter of 1944, probably the worst period in the camp’s history for two reasons. It was winter and bitterly cold, and Belsen was originally built for 6,000 people and in the end imprisoned nearly 10 times more. Epidemics of typhus, typhoid, tuberculosis and dysentery broke out, and many people, including my father, died of starvation. I remember the physical hardships; the hunger, the freezing weather and, to some extent, the boredom, because we had to stand around to be counted for hours, in the cold and wind. My mother (who had been put in a separate building from my father) would teach me to count, multiply and divide, and also some German words, which I remember finding odd because the Germans were the enemy.

The hunger was a constant. There was a brown liquid like coffee and a slice of bread in the morning, and we were fed a thin soup which contained vegetables and, if you were lucky, some potato. As the war went on and the Germans were losing, there was less food, and in the last few days there was none at all. When we did get some bread, my mother would give me only part of the ration, saving a little in case we did not get any the next day. Even after we were liberated in April 1945 and had plenty of food provided by the Americans, she would feed me gradually. She knew that if we ate a lot, immediately, our digestive systems wouldn’t take it and we could die for that reason. I don’t remember ever getting sick, which was a miracle.

Belsen wasn’t an extermination camp but it had a terrible reputation because of the overcrowding and the epidemics, and people died by the thousands. I don’t know if my father was buried in one of the mass graves, or cremated. My large family suffered heavy losses. Five out of eight siblings died on my father’s side and four out of eight on my mother’s. I also had a brother, who was 14 years older than me, who was taken from Hungary to do hard labour and died of typhoid on his return.

For a while my mother didn’t want to talk about the Holocaust but when I became a teenager I started to ask questions. Despite the infernal time we had, I don’t think I carry a psychological burden. I was a child and as an adult didn’t allow any hatred to grow. But I don’t blame those who did.

Lidia Vago

Lidia Vago was born in Romania in 1924. She was a 20-year-old French and English student when she and her sister were selected for a women’s work camp. They were liberated in May 1945.

We were marched to a row of huts, surrounded by electric barbed wire, that had no bunks, just wood floors and a leaking roof. This was the horrendous quarantine camp. It was a terrible place we would never have been able to imagine, even if someone had told us about it. We were defeminised: all our periods stopped. And we were given a metal bowl for five women to share but no spoon; so we had to sip this horrible soup-like liquid, taking a gulp and passing it to the next woman. We slept on the floor without blankets and after a few days everyone had diarrhoea. There was a makeshift toilet but we weren’t allowed to use it all the time, so we had to use the metal bowl for our physical needs; we washed it out in water so dirty, there was a sign above the ditch that read “Danger of epidemics”.

One of the women asked the head of our block, Hella, “Where are our family members?” and she pointed at dark clouds of smoke and flames in the distance [coming from the gas chamber]. Most of the women did not want to believe it, but I knew then that I’d never see my mother again.

On 8 July, we were selected for work (anyone who was found limping, or deemed unfit for work like my mother, was sent straight to the gas chambers). We were not human beings any more, we were numbers, and they were tattooed on our left arms. We worked 6am-6pm in a weapons factory in Auschwitz before moving to night shifts in October. It was hard work but it saved our lives. We were starving to death and when I became ill in December 1944, I was taken to hospital. A female doctor recognised me from our local town, and gave me and my sister cubes of sugar. I was in hospital for three weeks and I was forgotten about, but I was glad I didn’t have to work.

By January 1945, the camp was evacuated. My sister and I survived the three-day march to Ravensbrück concentration camp and were eventually liberated in May 1945. Our father, who had been taken to the notorious Ebensee camp in Austria [where cases of cannibalism were reported], died in an American military hospital the following month. And so he died a free Jew. Thank you, American GIs.

Aviva Cohen

Aviva Cohen was born in 1939 in Poland. Her mother and grandmother died at Auschwitz. She emigrated to America in 1951.

When the war ended in 1945, a man showed up at the house. By then I was six and I remember answering and telling Anna there was a Jew at the door and asking, “What is he doing here?” They explained that he was my father and I got used to having him around. I didn’t rebel or question anything.

Then it came to saying goodbye to Anna. My father’s version is that Anna was paid well to take care of me but I was in bad shape. In 2001, I was reunited with Anna and heard her story. She said my father arrived and, knowing my mother was dead, proposed to her. She said no, because he was 20 years older and she was still in love with my uncle. That hurt my father’s ego.

The atmosphere in Poland was horrendous. People came back to reclaim their houses and they were murdered. My father married another Holocaust survivor in 1946, had my sister the following year and they ran an orphanage together in Paris before we emigrated to the United States in 1951.

When I was reunited with Anna in 2001, it was as if we had seen each other the week before. She’s in her 90s now and hard of hearing, but she’s a tough cookie and she’s fabulous. When you think of how it started and where we are now, it’s a miracle.

Charles Srebnik

Charles Srebnik was born in Brussels in 1934 to Polish refugees. He started a new life in America in 1946.

I stayed at a number of orphanages before being reunited with my mother several years later, when she was working as a maid at the home of the Belgian underground headquarters. I came to live with her, aged 10, after she persuaded the underground that they could benefit from a young boy. I used to go out on a bike to the station at night and report back how many German trains had departed and arrived, and perform other errands; they never explained the reasons.

We were liberated in August 1944 by General Patton’s Third Army and for the first time in my life I felt what it was to be free. I could go outside without being afraid of the Germans taking me or my mother away; I could talk to others without thinking I had to keep secrets or be afraid they would know where I lived.

My mother died in 2004, in her 90s, never knowing what had happened to my father. She presumed he was murdered but spent much of her life looking for him, and even stocked up the cottage near the lake with food in case he went back there. She spoke easily about her horrific experiences. I think she felt the more she talked about it, the easier it was to live with. I found the opposite. But when she died I felt a responsibility to talk about it, although I still get emotional when I do.

Maria Lewitt

Maria Lewitt was born in Poland in 1924. In 1939 she moved into the Warsaw ghetto, the largest in Nazi-occupied Europe, with her mother and sister. She now lives in Australia.

My mother, sister and I left for Warsaw the following month and lived in the ghetto for over a year. There were half a million inhabitants; four rooms to a flat and a family in each room. There was a basin to wash in and a toilet on the landing. Basic staples of bread, potatoes, vegetables and, very occasionally, eggs were strictly rationed, as Jews in the ghetto got much less than the Poles outside. Every morning, I took leftover crumbs to the window ledge so the birds would come, and then I’d watch them fly back over the wall and be free.

Before my father died, he said to me, “The Nazis can take everything – our pictures, our books – away from us, but they can never take the things we learn and remember.” My teacher was also in the ghetto and she would teach five of us from our school in secret, because it was punishable by death to teach Jewish children. There were so many death punishments: buying and selling food on the black market, breaking curfew, even walking across the street the wrong way.

We left Warsaw when my older sister was entrapped and beaten by Jew hunters after we had left the ghetto and moved to the Aryan side. My mother’s (non-Jewish) sister Aleksandra had a house and garden in the countryside, and helped smuggle us out with false papers and new names in 1942; we stayed there in hiding until the war ended in 1945. I remember her saying, “Why are you staying in the ghetto? You know how to speak Polish. You have blue eyes and blond hair, get out.” My mother was annoyed with me for complaining I was happier in the ghetto, because my friends and my teacher were there; it also felt important for me to study as my father had wanted.

When we left the ghetto, I made a pact with my school friends that we would meet on a certain street corner in Warsaw after the war, but none of them turned up. They had all perished. Of my entire school class, I was one of only three who survived.

Sarah Capelovitch

Sarah Capelovitch was born in Lithuania in 1937. She moved into the Kovno ghetto with her mother after her father was murdered.

Dr Baron had connections and arranged for me, in 1943, to go and live with a gentile woman, Konstanza Brazeniene. My mother dressed me in the middle of the night, not knowing where she was sending me and if she would see me again. I was smuggled out at 4.30am in a crowd of women (including my mother and aunt) who were marching into a labour camp. We crossed a bridge, and on the far side I had to hide in a stationary cable car until Konstanza’s son came to meet me.

A few weeks later, all the women were taken to Stutthof concentration camp on the border of Lithuania and Poland. Many were raped and killed; few survived but my mother was one of the lucky ones. The Nazis took what was left of the Jews on a train to the gas chambers, but my mother fell off into the snow and was found half-conscious by Russian soldiers.

Some Christian families and priests never returned the children they rescued to their relatives, but Konstanza was happy to see my mother alive in May 1945 and we went back to the house where I was born. My mother had buried a tapestry made for my first birthday in a hole under the floor and now it’s the only thing I have left. I have no pictures of my ancestors, and I feel my childhood was robbed from me. Some people are haunted by Holocaust memories but what helps me is talking about it. The motto in our house was always to talk, not to suppress. You need to learn to forgive, but you don’t forget.

Originally published HERE