In recent years the Jerusalem Foundation has helped the Cafe Europa program establish locations throughout Jerusalem, where attendees can mingle, go on trips and take in lectures

From left to right, Dolly Tiger Chinitz, her husband Larry Frisch, Chaim Maltz, and Judy Maltz, regulars at the Cafe Europa in the German Colony. (Yaakov Schwartz)

Once a week, the Ginot Ha’ir community council in Jerusalem’s German Colony neighborhood is transformed into a bustling center for English-speaking Holocaust survivors from many countries — a place where they come to relax, enjoy recreational activities, and simply socialize.

One wouldn’t expect a haven to look like this: a roomful of smiling octogenarians speaking animatedly to one another, kibitzing, and noshing on cake — chatting loudly enough, in fact, that a reporter has to raise his voice to be heard.

Yet a haven is exactly what this is, designated for older citizens of Jerusalem who outside of these four walls represent one of the most neglected demographics in the country.

Many of Jerusalem’s Holocaust survivors live in poverty and have limited access to basic resources. In addition, many live alone and have little or no extended family nearby to help them.

And while the municipality has earmarked some funds for necessities, Dr. Adit Dayan, the Jerusalem Foundation’s director of community and social welfare projects, says that certain intangible benefits such as those offered at Cafe Europa program fall between the bureaucratic cracks.

The program — named after a cafe in Sweden where survivors would congregate to search for loved ones after the war — has branches strategically located throughout the city dedicated to different sectors of the population, with separate groups for ultra-Orthodox men and women, as well as one for the English speakers at Ginot Ha’ir.

Attendees mingle before an afternoon movie is shown. (Yaakov Schwartz)

Common to all the branches is the unique approach, which focuses not on gathering survivors into group therapy sessions but rather on providing a space for them to organically fraternize with people who share similar experiences.

“We wanted to salute these people in a positive way,” says Dayan. “To provide leisure time once a week, with lectures,

concerts, trips — to bring back some of the good memories they have from Europe.”

Dayan says that since this type of programming is not deemed essential, it is tricky to secure government funding. That’s why the Jerusalem Foundation has taken up the cause, providing over half a million shekels ($132,000) per year over the last seven years that helped Cafe Europa expand from one branch on Ussishkin Street into eight locations serving Holocaust survivors across the city.

Among the regulars at Cafe Europa are many “hidden children,” a name given to the young who were disguised and sheltered by non-Jews, masking their true identities in order to escape annihilation. It was not uncommon for these hidden children to have been through numerous concentration camps and orphanages, and to listen to the Cafe Europa participants counting them off on their fingers it almost seems unbelievable.

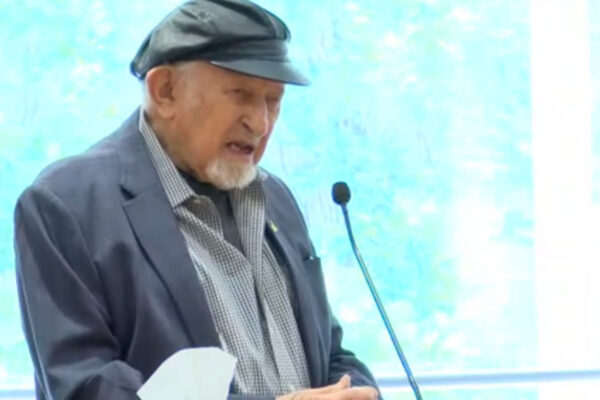

Kurt Judas, born in Germany, was deported to France on October 22, 1940, at age eight. He survived two concentration camps and lived in five orphanages, spending the last eight months of the war hiding his Jewish identity. His was the first bar mitzvah that his orphanage held after the war.

The Children of the Kindertransport sculpture, outside Liverpool Street Station in London (John Chase, 2006)

Judas met his friend Chaim Maltz at a reunion for 700 hidden children in Washington, DC. in 1991 when he was trying to collect 10 men for a prayer quorum. The two now meet weekly at Cafe Europa, a hemisphere away in Jerusalem.

“I think it’s great,” Maltz says. “It gives us a chance to mingle, talk to each other, rehash the past.”

At 80, Maltz claims to be the program’s youngest attendee.

Cafe Europa isn’t just a weekly meeting place, however. Volunteers and professionals provide a host of services to survivors who otherwise would have a difficult time navigating complex bureaucratic channels, accessing technology, and obtaining social benefits due them.

For those unable to leave their homes, home visits are available, with even a mobile computer workshop with internet access.

Also a regular part of the itinerary are events, excursions, and lectures, giving participants the opportunity to partake in experiences they otherwise wouldn’t have endeavored alone. The program even provides gift cards at holiday times.

‘We wanted to salute these people in a positive way, to bring back some of the good memories they have from Europe’

Significantly, the trained social workers are able to identify the specific needs of each survivor, treating them individually under the auspices of the social welfare bureau.

Social worker Avia Bruckental-Friedlich credits the Jerusalem Foundation with helping grow the program from a fledgling outpost to a citywide phenomenon.

“The Jerusalem Foundation was involved from the beginning,” she says. “Eight years ago we started with one Hebrew-speaking group, and we have enjoyed a tight relationship since.”

“I don’t speak Hebrew yet,” says Gerta Solan, an 86-year-old Czech survivor and new immigrant who moved to Israel a scant two years ago. “I like this group because it lets me find friends who I can speak in English with.”

Gerta Solan made aliyah a mere two years ago from Canada. (Yaakov Schwartz)

Solan’s recent move was significant, but not the most jarring of her life. Born in Prague, she spent three years in a concentration camp before returning to the city of her birth — only to find it occupied again in 1968, this time by the Soviet army. She fled to Toronto with her husband and 14-year-old son, where she lived for over 45 years before relocating to Israel.

But the survivors themselves aren’t the only ones with fascinating tales — nor are they the only ones to benefit. First-time volunteer Anne Schiff was born to a pair of Czech and Hungarian survivors in Australia, where Hungarian was her first language.

She left Australia for the United States in 1984, where she became a professor of law at the University of Pittsburgh. Her family made aliyah seven years ago.

“I was looking for opportunities to work with survivors,” she says. “It’s really such a privilege — each and every story is a miracle.”

Originally Published HERE