by Shelby Curran

It’s taken me two months and six days to understand. To question. To think. To feel. And ultimately, to process.Most of us on the trip journaled in one way or another. Whether it was in the form of picture taking, writing, or collecting keepsakes, every teen made an effort to remember. It’s no secret that I keep moments alive through writing. I’m a median for words, a sucker for travel diaries, and a lover of crossed out sentences and messy scribbles. On every other travel experience I have embarked on, such as a community service program in Chicago or countless summers at camp, I have written endless pages about things that happened on the daily. But on the March of the Living, my hands were paralyzed, my pencils were dormant, and my mind was flustered. Instead of a collection of testimonies from my time in Poland, I boarded the plane with a journal filled with a few paragraphs, some quotes, several bullet points, but mostly empty pages. It may not seem like a big deal to others, but to me, it was the strangest thing the world.

It’s taken me two months and six days to understand. To question. To think. To feel. And ultimately, to process.Most of us on the trip journaled in one way or another. Whether it was in the form of picture taking, writing, or collecting keepsakes, every teen made an effort to remember. It’s no secret that I keep moments alive through writing. I’m a median for words, a sucker for travel diaries, and a lover of crossed out sentences and messy scribbles. On every other travel experience I have embarked on, such as a community service program in Chicago or countless summers at camp, I have written endless pages about things that happened on the daily. But on the March of the Living, my hands were paralyzed, my pencils were dormant, and my mind was flustered. Instead of a collection of testimonies from my time in Poland, I boarded the plane with a journal filled with a few paragraphs, some quotes, several bullet points, but mostly empty pages. It may not seem like a big deal to others, but to me, it was the strangest thing the world. A best friend put it best when she told me, “You are someone who processes experiences and feelings when you write. So write when you get home. You’re not ready to dissect it yet. Take it in now, but don’t force yourself to understand. Experience now, and process later.”That leaves me at two months and six days later. The jet-lag is long gone. The suitcases are unpacked. The Facebook notifications tagging Jewish teenagers with Israeli flags draped around their backs by the gates of Birkaneu have ceased (aside from the throwback Thursdays, of course). And only now am I just starting to pick up my pencil. To process. To feel something bigger.

A best friend put it best when she told me, “You are someone who processes experiences and feelings when you write. So write when you get home. You’re not ready to dissect it yet. Take it in now, but don’t force yourself to understand. Experience now, and process later.”That leaves me at two months and six days later. The jet-lag is long gone. The suitcases are unpacked. The Facebook notifications tagging Jewish teenagers with Israeli flags draped around their backs by the gates of Birkaneu have ceased (aside from the throwback Thursdays, of course). And only now am I just starting to pick up my pencil. To process. To feel something bigger.

Truthfully, any teen who has participated in this incredible experience could write a novel about what they saw, heard, and felt. While every person leaves with a different outlook on the March of the Living, these experiences are not only mine, but the community of those who traveled with me. After all, it changes someone— walking into a hell that so many wanted to escape, and being able to exit the gates when so many others were not as lucky. But clearly, this is a blog entry, not an autobiography. (Even though it is really freaking long, so brace yourself.) I’ll recap some of the bullet points and sentences that I wrote while in Poland, while adding some of the testimonies I should have written:

A half of a sleeping tranquilizer doesn’t cut it. Never fly economy on an international flight. Aim for 48 pounds, not 50 pounds. I swear, the airport’s scale is lying. Don’t question the seriousness of the name tag. Just wear it. From the air, Poland looks like the houses in an iPhone game app I am addicted to: Hay Day. Also, does everyone have a pink roof here?“So, you’re about to embark on a bad ass emotional journey. Please don’t sweat the small stuff. In the end, you won’t remember how exhausted you were or how shitty the food was. So make friends, don’t be afraid to feel, and learn something.”

A half of a sleeping tranquilizer doesn’t cut it. Never fly economy on an international flight. Aim for 48 pounds, not 50 pounds. I swear, the airport’s scale is lying. Don’t question the seriousness of the name tag. Just wear it. From the air, Poland looks like the houses in an iPhone game app I am addicted to: Hay Day. Also, does everyone have a pink roof here?“So, you’re about to embark on a bad ass emotional journey. Please don’t sweat the small stuff. In the end, you won’t remember how exhausted you were or how shitty the food was. So make friends, don’t be afraid to feel, and learn something.”

“It seems crazy that I’m finally here. After years of having ‘Holocaust’ and ‘March of the Living’ drilled into my vocabulary, it’s finally my turn to experience this. I’m sure the classes I went to on Sundays will help me foster a stronger connection to some of the places I will visit, but no amount of education can prepare anyone emotionally for this. But, maybe it’s better that way: to be raw, in the moment, and not have any idea what to expect. This way, the reactions are natural. Then it’s real, candid. I want that. I want to understand everything that my grandmother, a Holocaust survivor of Auschwitz-Birkaneau, has been through. She’s been on this same trip over ten times, and I don’t know how she can come back. It’s my job to tell the story when she’s gone. I want to reconnect with my Judaism before college. Maybe I’ll find my calling. Or maybe I won’t, but either way, I want to feel purpose.”

“Treblinka was….

beautiful. peaceful. content.

Birds chirped, trees grew, life existed.

But underneath the freshly paved pathways are bones, blood, tears, history. There was an 18 minute life expectancy here. From arrival, to death. 18 minutes. In Judaism, 18 is a number that represents life. How ironic. In the field of Treblinka was a memorial site of stones, each one representing a town or population of Jews that was murdered. I don’t know what I expected. Burnt down rubbles? Gray skies? A stench of death? Nothing. In Treblinka, there was absence. And then, when I blocked out the sound of the bird calls and focused on the howling of the wind, it wasn’t peaceful anymore. The absence became the screams of 840,000.”

“Today, we visited the oldest Jewish cemetery in Europe. Here in Warsaw are the grave sites of many Jews who were buried before the war. It is evidence that life here was normal, thriving, and complete. There are symbols on the gravestones representing the individual’s personality and interests: shabbat candles for religious women, or books for writers. I thought about it, but I’m not certain right now what I would want to be remembered for. Years later, teens from the Warsaw ghetto smuggled dead bodies through sewers inside of the cemetery to bury those who had died behind ghetto walls and were unable to have a proper burial. Judaism has strong beliefs about honoring the dead, but I don’t think I would ever have the courage to risk my life like that, especially for someone lifeless. Would they even know the difference? Does that make me terrible? I don’t think so. I just think it makes me fearsome.”

“We walked silently to a train stop where thousands boarded to their death. There was a memorial honoring over 300,000, and engraved in the stone were a myriad of common Jewish names. We each picked a name to shade onto a sheet of paper with a crayon. I chose Chana because it was my grandmother’s original name. I put it inside of my name badge so that all of the Chanas would travel to Israel with me. You know, since they never got the chance.”

“We walked silently to a train stop where thousands boarded to their death. There was a memorial honoring over 300,000, and engraved in the stone were a myriad of common Jewish names. We each picked a name to shade onto a sheet of paper with a crayon. I chose Chana because it was my grandmother’s original name. I put it inside of my name badge so that all of the Chanas would travel to Israel with me. You know, since they never got the chance.”

“We are celebrating Shabbat in Warsaw. We walked to a very old synagogue to be joined by hundreds of others from different March delegations across the globe. On the way, we passed by a building that Jews in the ghetto lived in. There were even bullet holes. It felt real. Then, I saw a graffiti picture of a big nosed smiley face. Anti-semitism is still here. Hate is still here in Warsaw.”

“During the service, a 96 year old man celebrated his birthday by chanting Torah. I liked that very much. I also met a few girls from Canada, and they told me which boots to buy and how to survive cold weather when I move to Chicago for college.”

“At a memorial site for the Jews of Lodz, one of the survivors on our trip, Adele, was surprised with a tree dedication. It was priceless to see her hugging it and dancing around it. She was told that a tree is like a home, and that even though she was forced out at a young age, she will always be a member of the town. We sang and danced around the tree. It was truly a moment.

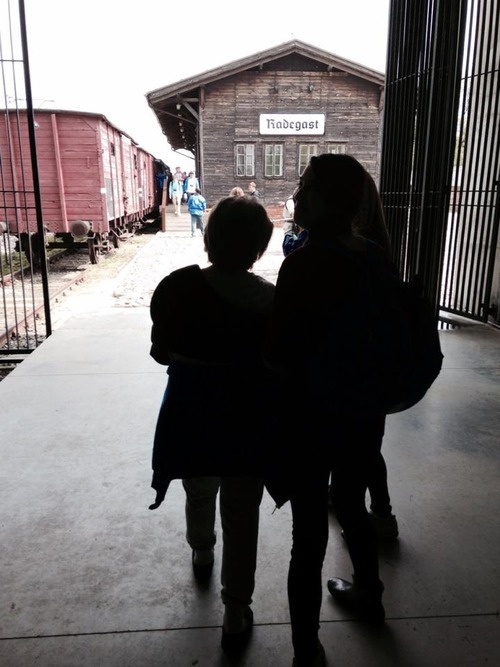

“For four days, I hadn’t felt very much. I always thought that the first emotion I would experience was sadness, but in Radegast, a train station in Lodz where people were deported to camps such as Auschwitz, I was not sad. I was pissed off. I was mad and I was frustrated and I was angry, because I didn’t find what I was looking for.

Lining the walls of the memorial tunnel are names of the Jews of Lodz, like a roll call or registration list. A girl named Sabka that my grandmother befriended in the camps was from there My grandmother told me that she had never found her name, and that after years of looking, she had given up. I looked through every single name listed, but I couldn’t find it. I cried because I was so frustrated. I cried because I wanted to find Sabka’s name so badly, but there were too many pages. My grandmother tried to calm me down, explaining that she didn’t know Sabka’s last name, and that it could have been a nickname anyways. It was impossible to know her full name for certain— whose to know if an Allie’s real name is Allison, Alexandra, Alyssa? But I felt like I had failed her.

At the station, my grandmother led some of the teens into one of the cattle cars and spoke about her time there. A hundred people in one small, enclosed area with no windows, no light. No toilets, only a bucket. No food, and no water. Later, on the track, she lit a candle for Sabka and her family, and others who had died while inside the cattle cars. And I cried.”

“Never have I ever seen an old person run so fast. We brought Adele back to the apartment she had lived in as a child before the war. The street was so beautiful, with modern day shops and Polish children biking. When we reached the court yard, Adele’s face lit up like the sun. She eagerly showed us where she used to play, and told us about when her mother used to call out the window to tell her that it was time for dinner. In that moment, I swear, she was a kid again. You should have seen it. We all were kids again, naive and infinite.”

“Tonight is Erev Yom HaShoa, the evening before Holocaust Remembrance Day. We attended a ceremony honoring survivors from North American delegations. My friend read a beautiful poem in honor of my grandmother, regarding her experience in the cattle car. She read, ‘Today, Irene was brave for us. But today, I wanted to be brave for Irene.’ I had felt that way my whole life. My grandmother had done so much for me. Today, she held me when I cried by the railroad tracks, but I should have held her. Today, I also wanted to be brave for Irene. But the fearless do not need anyone to be strong for them. They are powerhouses; my grandmother is a powerhouse.”

“My grandmother makes baby blankets. I always thought that was because old people usually like to knit. However, today she told me that where she worked outside of Birkaneu, in a place called Canada, she sorted baby blankets for the Nazis that had previously belonged to Jewish children. Now, she makes a baby blanket for every newborn she knows to compensate for it.”

“My grandmother dislocated her shoulder earlier this trip, but she is a trooper. I had to help her shower tonight because she can’t lift her arm to put shampoo in her hair. A week ago, I would have been annoyed that I didn’t get to spend the rest of the time before lights out with my friends, but now, I’m finding myself valuing the time that I have with her. I can’t believe I never realized how much we are alike. Stubborn and strong willed. Broken, but bad ass. Dislocated, yet complete.”

“We all laughed behind the gates of Auschwitz. Isn’t that strange? The march is from Auschwitz to Birkaenu, three kilometers long. During the Holocaust, prisoners were forced on death marches, and ironically, this is the march of life (hence the March of the Living.) Thousands of passionate Jews and supporters from all over the world are about to walk in the same path, the same footsteps. So when first we laughed behind the gates of Auschwitz, I was disgusted. How could we be happy in a place like this? But after a while, I understood the real significance behind the March of the Living. We were not here to wallow in sadness and pain, but to celebrate the strength of our people.

After marching, some friends and I placed our decorated paddles into the crevices of the railroad track along hundreds of others. We lit memorial candles. I can’t explain that moment. I can’t explain to anyone because there aren’t any words, really, just feelings. Awe. Because we sat outside the gates of Birkaneu and watched hundreds of people with Israeli flags willingly march inside the gates. Willingly. Because to the left of me there was a man wearing a kippah from Brazil, and to the right there was a woman speaking in an Australian accent. Because as I sat in silence and cried with my best friends, the buses that the survivors arrived on, since they were unable to walk the three kilometers, drove past. We saw Adele waving to us. Because when we cried, she smiled.

My grandmother called me over to the pile of rubble that had been a gas chamber. We lit a candle and the entire delegation watched. I was supposed to feel empowered by everyone standing there, but I just felt uncomfortable. ‘Don’t worry,’ my nana assured me. ‘It’s okay if you hear or see something, it is just my family talking to you. They want to meet you. You may not experience anything, you might just feel a presence.’ I had no idea what she was talking about or what to expect. She sounded crazy. I felt weak.

And just when I thought it couldn’t get any more insane, my grandmother pointed at the caved in entrance of the gas chamber and exclaimed, ‘Here they come now!’ I was horrified. All at once, she started speaking in Hungarian and gestured towards me, as if introducing me to an old friend. After a minute or two, she started to sob. Not just to cry, but to bawl. ‘My mother said that you are so beautiful. You have her eyes. Don’t you see? This is where your family was taken away from me.’ I stood there, with fifty people watching and crying, and tried to understand. I wanted to cry, or be sad, but I was just freaked out, because my grandmother had just spoken to ghosts or something. I wanted to cry, but I just shook, because I didn’t know what to do. I never knew what to do. Is there a right thing to do?

Today, I walked my grandmother out of Birkaneu. Today, I brought her out of hell. And I know that we needed her more than she needed us, but it was best I could do. It was all I could give. I tried to be brave for her. Today, we all made it out. Today, I walked my grandmother out of Birkaneu. That is something. Today, I am a powerhouse.”

“I have envisioned this moment for the past year. ‘When you are inside of the gas chamber, take a moment to put your head against the wall. Close your eyes and listen,’ grandmother told me time and time again. It sounds simply, really. Instructions. A check list. Procedure. But there is no order in hell.

We were in Auschwitz and just about to go inside of the gas chamber. I was walking arm in arm with friends, when my grandmother called me over. ‘I’m going in.’ Three words that meant so much more. My grandmother has been on this trip for over a decade. She has returned to Auschwitz over a dozen times. She has had the opportunity to go inside the chamber of death many times before, but never had. How could she? Her entire family perished here. It brings back haunted memories and ghosts of the past. My older sister and my mother had both gone on the March of the Living with her, just like this, yet entered the chamber alone, without her. But with me, she wanted to go inside. With me. Why me?

I must have asked her if she was sure a million times. ‘If I freak out, don’t worry, keep going. If I turn around, don’t follow me, face the darkness. But I will try. For you.’ Am I the favorite or something?

And we walked. ‘Be careful, Irene. There is a step coming up. It’s dark and it is hard to see,’ one of the teens warned her.

I looked at my grandmother and her eyes were wide, her palm shaking against mine. ‘It’s not dark. It’s light. It is very clear here, it is very clear to me. I see everything.’

It was hands down one of the creepiest and scariest things I have ever experienced. I wanted to scream, to shake her, to leave. But when she turned around just steps before the entrance, I was alone for a moment. Scared. Suddenly, someone started singing the Hatikvah, Israel’s national anthem, and others joined in. A chamber of death that had once echoed with screams and cries and final breaths, now rung with the song of Israel. The song of freedom. The song of redemption, or triumph. I felt okay. Empowered. I was okay.

So, I crouched down and held my best friend’s hand. I put my head against the wall. I closed my eyes, I listened.

I don’t know what happened next, but all at once, I couldn’t breathe. I didn’t really hear anything or see anything or feel anything specific. I just needed to get out. I can’t tell you what happened in there, and I don’t know what happened in there. But for a while, every fiber in my being was different. I felt differently, moved differently. The psychologist on the trip calmed me down, and had told me that I had my first panic attack. I knew I would be somber on this trip, but I didn’t know I would be scared.”

“You can see the city from Majdanek. They didn’t kill people in the middle of nowhere, like I had thought. You could see roofs from the bunkers. The citizens of the town smelt the stench of death and cleaned remnants from the crematorium from their windowsills, they say. That made me naseous.

The engraving on the dome translates to ‘our faith is your warning.’ And in the center of the statue were ashes and bones of the victims. Mothers. Uncles. Grandmothers. Brothers. Friends. PEOPLE.

I sat on the ledge and cried. There was nothing else to do. In a few hours, I would be boarding the plane to Israel. I would escape hell, I would be back to reality. But in that moment, I sat on the ledge and cried, next to human ashes of my ancestors. And as twisted as this sounds, I never want to forget what that felt like, what it was like to feel so moved, that you were brought to tears. So, I kept sitting on the ledge. And I kept crying.”

After highlighting and absorbing a few of the many moments experienced on the March of the Living, there is so much more that I now understand and know. But there are also many things that I continue to question and struggle with.

I understand that there is hate in this world; I know that there is also love.

But I have yet to answer the question as to why the good doesn’t always trump the evil.

I understand that too many innocent people died; I know that they are honored and remembered.

But I have yet to answer the question as to what exactly will be my role, not only as a Jew, but as the granddaughter of a Holocaust survivor, in Holocaust education and keeping history alive.

Maybe I’ll write an afterword to my grandmother’s book, The Fifth Diamond, about her life following the war. While the novel tells her story of survival, maybe I’ll tell her story of revival, and about how she is sharing her testimony across the country and impacting every person she has come in contact with.

Maybe I’ll make a hip friend in college who is a film maker and help to adapt a movie script, continuing to educate those on the Holocaust.

Maybe I’ll return to Poland with the future generation of teens with the March of Living as an educator.

Maybe I’ll do all of those things, or none of those things, find something else that clicks.

I don’t know what my calling will be, but I now know my purpose. After all, it will be up to me and my peers to keep the memories alive after all of the survivors have passed on.

It’s been two months and six days since I left Poland. And each day, instead of allowing the memories to become lost in the routine of everyday life, my thoughts are only becoming more clear and vivid.

It’s taken me two months and six days to understand. To question. To think. To feel. And ultimately, to process.

I have understood that the purpose is not to hate, but to show what hatred can do. I have questioned what my service to the Jewish people will be. I havethought about the meaning of life, and the limited number of our days. I havefelt more alive than I have in all of my eighteen years of existence, in a place that, ironically, was filled with more death than I have ever known. And ultimately, I am continuing to process flashbacks of barbed wire, crying on friends’ shoulders, and panic attacks inside gas chambers; both through my own eyes, and through my grandmother’s.

There is not a day that goes by that I don’t think about the March of the Living. Some days, I am sad for lives lost. Other days, I am proud to be a Jew. Every day, it’s different. But every day, there is a significance. Today, that significance was to pick up the pencil and write. To start processing. It wasn’t about elegance or perfection. Some sentences don’t right just yet, and some words are wrong because it’s hard to transfer feelings into vocabulary. But as I am able to process more and more, I’ll be able to explain more and more. To be more and more. After all, today was about the beginning. Today was about telling the story. And who knows? Maybe tomorrow will about getting it right. It’s my start, and I think that’s what counts.

It’s been two months and six days since I left Poland. And today, I picked up the pencil.