By: Varda Epstein, The Huffington Post

What would it feel like to have no family tree? To not know who your parents were, or where you come from? In so many ways, our families define us.

For instance, my Asiatic eyes and fair coloring come from my father, but my droll sense of humor and literary mind are from my mother. As such, I feel the responsibility to hand down these qualities to my own children. We are part of a chain held together with crumbling photos of long-dead relatives.

There is something addictive about old family photos. You look at them and wonder if those sepia creatures had the same thoughts and dreams, loved hard, felt the tug of an infant’s mouth at one’s breast, knew fear, success. You want to know if they had gifts, the nature of them, and if you might have been lucky enough to inherit a small (or large) measure of that very same talent. You want to know their medical histories. You hope they weren’t criminals.

Mysterious Photos

But sometimes those photos are a complete mystery. Stare at them all you want, but there will be no clear message telling you the identities of the faces and figures they depict. There will be no clues. You won’t know why this or that photo came to you or how it ended up in your possession.

I began to explore my family tree in 2001. I’m part of a wave of Jews who returned to their heritage and embraced the orthodoxy our grandparents more or less rejected. It was difficult for them. They were greeners, some of them, and needed a way to fit in. The trappings of the religious and their Sabbath day didn’t fit the culture of the America that threatened not to accept them if they were a little too different. Off went the wigs, while Sabbath observances were reconfigured to fit their “modern” circumstances.

When I became orthodox, it was a different time. Freedom of expression was in vogue, as was returning to one’s roots. Still, my family was not thrilled when I became religious and figured it was a stage that would pass.

It didn’t.

Something Unsavory

But as I grew older and had children of my own, I found that I had unwittingly joined a culture that looked down on me, because my family had cut ties with orthodox observances. My children were less marriageable, and there was something unsavory about us.

I didn’t like it.

Researching my family tree helped me identify the rabbis in my line, and made me feel better about my place within my people. That’s why I researched my family tree. And it made a difference for me. It made a difference in how I saw myself, and how I felt as I walked in the streets of Jerusalem. I now owned these streets as much as any Jew.

That’s what family research did for me. It made me hold my shoulders high. It gave me back my pride.

So when I heard about Pnina Gutman, I could feel what she felt. Here was a woman who changed hands so many times during the Holocaust that no one knew who her parents were. It was a miracle she had survived, and yet a cruel miracle, for she didn’t know who she was. She looked in the mirror and wondered and it was like looking at those photos that end up in your things and you don’t know how you are connected to them.

When Pnina was nine months old, her young parents convinced a German soldier to smuggle their baby daughter out of the Warsaw Ghetto to safety. This was in1943, just before the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. Pnina’s parents would have come from Germany or from a German-occupied town in western Poland. These were places from which Jews were deported to the Ghetto.

The soldier took the baby to his girlfriend, Sonia Spyra. The baby was in a white baby carriage with a note hanging from her neck with the name Barbara Wenglinski written thereon. Sonia took the baby to Charlotta Rebhun, a Christian woman with a Jewish husband, for safekeeping. Pnina had a vague memory of Charlotta’s handsome son, Wolfgang.

Instead of a response, an emissary from the Jewish Committee came to the Kaczmarek home and took little Barbara to an orphanage in Otwock. At age 6, Barbara was adopted by Mania and Mendel Himel. Introduced to them as “Basia,” the Himels renamed her Pnina. The year the young girl turned 8, the family made aliyah to Israel, where Pnina grew up, got married, and had a family of her own.

How did I come to be writing about Pnina Gutman? A friend, Israel Pickholtz, is a pioneer in the field of genealogy by DNA and wrote a book on the subject, Endogamy: One Family, One People. I read the chapters as my friend wrote them, and offered my comments. As an expression of gratitude for my small contribution, Israel purchased three DNA test kits: one for me, one for my mother, and one for my mother’s first cousin, the only male KOPELMAN left in our line.

Melody Amsel-Arieli, a genealogist and blogger, received a notification from Family Tree DNA that my results had us as fourth cousins. Furthermore, Melody discovered that both of us are related to Pnina Gutman, about whom Melody had blogged hereand here. Melody wondered if I knew of a young married couple from western Poland who had been left behind in Poland.

Whatever the identity of Pnina’s real parents, their final words, according to Wolfgang Rebhun were, “If we do not return, contact our relatives in America.”

It is a virtual certainty that Pnina’s real parents perished along with any close relatives she might have had. No one came forward to claim her at the war’s end. DNA tests suggest that Pnina has many distant relatives, including this writer and Melody Amsel-Arieli, with most of them having roots in northern Poland. In spite of these DNA matches, no actual relationships to any of these people have been verified.

At 73 years of age, Pnina has no name, no place of origin, and no family tree.

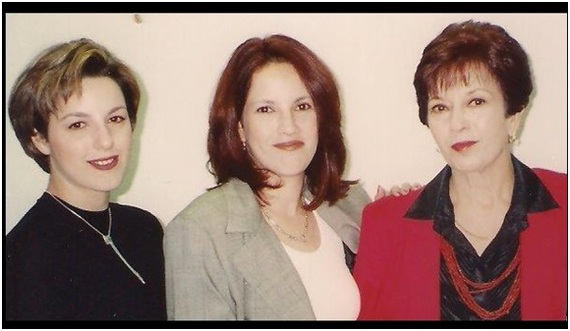

Do you have a photo of Pnina stashed away somewhere in a file drawer? Please, if you have even a small clue, suggestion, lead, or idea, contact Pnina Gutman so that she might finally be able to answer the question: Who am I and what is my name?

And share this piece like crazy.

It’s the least we can do.

Original Article HERE