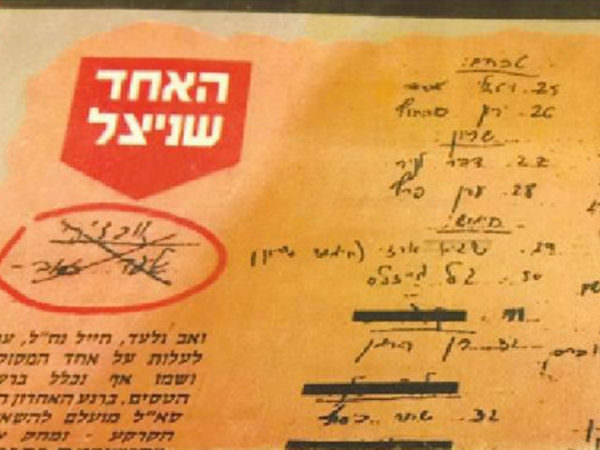

A copy of the list of soldiers who boarded a helicopter that crashed with a second one over Israel in 1997.

In February 1997, just over 20 years ago, headlines carried the news of the tragic crash of two helicopters over northern Israel, resulting in the deaths of 73 young Israeli soldiers. All of Israel, together with Jews around the world, mourned the loss of so many of Israel’s soldiers, most of them in their late teens and early 20s.

A friend of mine recognized the last name of one of the casualties that appeared in the newspaper. It was the same last name as that of a fellow South African oleh to Israel, Jonathan Misheiker, whom he first met at Hebrew University in the early 1960s.

A long-distance phone call to Israel confirmed his fears. “Yes, it was my 20-year-old son, Gilad, who was one of those who fell in the collision,” confirmed the faint voice on the other end of the line.

“But I’ll tell you something else,” the father continued. His son’s name had mistakenly appeared twice on the manifest containing the names of all the soldiers scheduled to board one of the helicopters. As a result, the commanding officer thought he had one too many men on the helicopter and ordered one young soldier to return home. The disgruntled soldier, forced to hitchhike home, did not realize how close a brush he had just had with death. “So,” the father concluded, “my son’s death was not entirely in vain. Because of him, the life of one more young Israeli soldier was saved.”

This story reminded me of Holocaust survivor and writer Viktor Frankl’s thoughts on suffering. Frankl proposed that the ultimate quest in life is not for pleasure, fame, power or wealth. The ultimate goal, he argued, whether we are aware of it or not, is to uncover the meaning in our lives. Despair, he would say, is suffering without meaning. Choosing what to do with one’s suffering, and choosing to go on living with meaning in the face of suffering, is the essential challenge and achievement for all human beings. It is this sense of meaning that enables people to overcome painful experiences.

In Genesis, we are told that Jacob, prior to his reconciliation with Esau, is wounded by a mysterious adversary as they struggled in the dark of night. But Jacob refuses to release his opponent from his grasp until he blesses Jacob, renaming him “Israel.”

Jungian therapist Esther Spitzer contends that Jacob refused to leave the scene of his injury until he found meaning in his suffering. The pain of his wounds was only tolerable if some consolation emerged from the struggle. Only after receiving his new name, and a new understanding of the meaning of his existence, does Jacob/Israel limp away to meet and make peace with his brother Esau.

Indian Jesuit and psychotherapist Anthony de Mello tells the story of a woman who came to the Master in great distress over the death of her son.

He listened to her patiently while she poured out her tale of woe. Then he said softly, “I cannot wipe away your tears, my dear. I can only teach you how to make them holy.”

The attempt to find some seed of consolation even in the grimmest moments reflects the truism that pain is made somewhat more bearable when we are able to find even a single thread of meaning, even as we endure our suffering.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the example of what Holocaust survivors throughout the world did in the aftermath of the war. Considering what they had undergone, who could have faulted them for giving in to despair and cynicism? Yet, they went on to rebuild their lives, start new families and become active contributors to their communities and society as a whole.

In deciding to return to life, survivors demonstrated exceptional fortitude, courage and faith. To quote Nobel Prize winner and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel, “To be a survivor after the Holocaust is to have all the reason in the world to destroy, and not to destroy. To have all the reasons in the world to hate, and not to hate… to have all the reasons in the world to mistrust, and not to mistrust. To have all the reasons in the world not to have faith in language, in singing, in prayers, not in God – but to go on telling the tale, to go on carrying on the dialogue and have our own silent prayers and quarrels with God.”

Despite their disappointment in the world, most survivors did not become embittered. While many did and still do wrestle with their faith, the vast majority of survivors did not give up faith in life itself, in the capacity for humanity to renew itself and to learn from past mistakes. To return again to Viktor Frankl: they imbued their lives with meaning, even as events of the Holocaust remained at the forefront of their consciousness.

They did not give up hope.

I remember a particularly difficult day almost 30 years ago, on my first March of the Living, in the former Majdanek concentration camp, one of the starkest and most visible reminders of Nazi cruelty. We concluded our visit by davening Minchah opposite the barbed wire fence, then boarded the buses and headed back to Warsaw. One of the chaperons later reflected that, for him, the moment summed up what it meant to be Jewish: to look straight at the barbed wire, and then to look past it, to the future. In short, he said, being Jewish means never giving up hope.

As we observe Yom Hashoah and Yom Hazikaron this year, let us honour the courage and resilience of our elderly survivors and our brave soldiers.

And let us also be thankful for the dedication of so many young people who, like the March of the Living participants, listen attentively to our survivors, carry forward the torch of memory, continue to practise Judaism and demonstrate their love for Israel.

They, too, fill our hearts with hope.

Eli Rubenstein is national director of March of the Living Canada.

Originally published HERE