Timothy Snyder describes Hitler as a leader who wanted to foment an ecological revolution in a global landscape with no place in it for the Jews.

“Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning,” by Timothy Snyder, Tim Duggan Books, 462 pages, $30

Upon the release of “Black Earth” this past September, historian Timothy Snyder wrote the following on his Facebook page: “Everything that I can do as an historian is in this book. Everything that I hope for as a human being is in this book.”

He ought to be admired for his sincerity. Without a doubt, Snyder invested estimable intellectual effort in this book. What emerged, however, is a problematic, confusing and at times erroneous narrative, but one that is above all overreaching. It ignores decades of research spanning countries, scholars and disciplines. “Black Earth” positions the Holocaust in a world of trivial, anachronistic definitions, and makes it harder to properly understand the formative historic event of the 20th century.

Snyder, who teaches contemporary Eastern European history at Yale University, gained fame outside of the academic world following the appearance of his 2010 book “Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin.” In that work, he placed the Holocaust in a broad framework of historic and territorial analysis – as an event that took place in an Eastern European expanse that was controlled in the 1930s and 1940s by two brutal totalitarian regimes: Stalinism and Nazism. His conclusion, which is based upon a comparative foundation, is thought-provoking. The two vicious regimes sustained one another, notwithstanding the violent clash between them that began in 1941. The murderous infrastructure that the Soviets had built up in areas of Ukraine, Volhynia, Belarus and the Baltic states subsequently served the Nazis in the same exact territories.

“Bloodlands” offers several important perspectives: the need to compare acts of genocide that share similar components (and also different ones, for sure), and the introduction of the spatial variable into study of the Nazi and the Stalinist genocides. Space is not just a geographical variable: Space has human, topographic and cultural foundations, all of which are components that shape the actions of the murderer, his victim and the third-party observer. Generally, study of the Holocaust barely relates to the spatial aspect.

“Black Earth” is also about the Holocaust, and it builds upon a thesis that was initially developed in “Bloodlands.” Any book that aspires to provide a comprehensive explanation for the Holocaust must begin with Hitler and with Nazi ideology, a field of study that is already super-saturated in the scholarly world; it is doubtful if anyone could add anything new to it. However, Snyder proposes taking a new direction – and the result is problematic. He contends that Hitler, whose worldview was shaped by the prevalent Volkist and anti-Semitic literature of the 19th century, was a revolutionary who was interested in fomenting a global ecological revolution that had at its core the annihilation of the Jews, a group he considered to constitute the worst ecological danger of all, one that would ultimately bring the human race to extinction.

Hitler indeed hints to something like this in “Mein Kampf,” but it is doubtful if what he intended is compatible with Snyder’s interpretation. Hitler wrote that if the Jew were victorious, the planet would revert to being devoid of human population, as it was millions of years ago. This is most assuredly an apocalyptic vision, but the connection between it and war of a global-ecological nature, as Snyder contends, is rather farfetched. There is no real evidence of such a connection in anything else that Hitler either said or wrote, and certainly not in his actions. In Hitler’s worldview, the Jew is a racial danger, and the Jew’s liquidation is therefore a biological need in safeguarding the human race.

Conversely, Snyder disregards the fact that Hitler created, first and foremost, a political movement. When he writes that Hitler was not in fact an extreme German nationalist but rather an ecological revolutionary, he pulls the ground out from under the primary basis of the Nazi movement as a political one, with an extreme-nationalist worldview that championed first and foremost the German nation, race and state.

The bottom line is that Hitler’s political ideological objective was to destroy the Soviet Union and its so-called Judeo-Bolshevik regime. Snyder states that to that end, the Fuehrer was initially prepared to make a far-reaching arrangement with Poland, had he been convinced that the Poles were willing to join him in an attack on the Soviet Union. When, in 1939, he came to realize that that would not transpire, Hitler formed an alliance with Stalin so that he would be able to destroy the Polish state and at a subsequent stage, attack Russia. The alliance with Stalin was a tactical and temporary move in order to solve the military problems with France and the U.K. Ideologically, the Soviet Union was Nazism’s major enemy.

For its part, argues Snyder, Poland wished to be rid of the many Jews who lived in the country, and was willing to agree to any arrangement – including one with Germany – that would lead to the mass migration of Jews from its territory. But when Poland understood that the migration would not happen, it was not willing to hitch itself to the German cart and risk undermining its relations with France and England, or risking war with the Soviet Union.

Poland a parter?

There are a few things here that don’t quite add up. The first and most important has to do with Hitler’s attitude toward Poland. Can we really believe that Hitler wanted to reach agreement with the Poles, and decided to liquidate the country only when he became convinced that no such alliance was possible? Even before the Nazi rise to power, and much more so in its aftermath, German scholars holding social-Darwinist racial views released study after study aimed at proving that Poland was a state that lacked any right to exist. In their opinion, Poland was doomed to collapse because it was Slavic and because of its many numerous minorities and primitive economy, but mainly because of the three million Jews living there. Leaders of the Nazi movement read these studies and even provided the financial underwriting for them. How could Poland be considered a partner in a war against the Judeo-Bolshevik enemy when it itself was rotten to the core because of the many Jews who lived there?

The introduction of the issue of the Zionist struggle in Palestine into this thesis is strange to say the least, and it is not at all clear why it was needed. Snyder claims that Poland’s support for the establishment of a Jewish state was a significant component of its foreign policy. This was the preferred option in Poland’s efforts to be rid of its Jews. We read very little in the book about the blatant anti-Semitism that was current in Poland of the 1930s. Instead, we learn about an alliance (if it could even be called this) between the Jewish Revisionist movement and the Polish regime, which helped members of the movement with arms supplies and military training.

In this story, Snyder elevates Avraham “Yair” Stern to the status of first-rank leader, who assumed a representative role in the effort to fulfill the vision of the Jewish state, with the help of the Poles. Not David Ben-Gurion, not Chaim Weizmann, not Ze’ev Jabotinsky, none of whom are even mentioned in the book: Stern is the prominent Zionist leader. It is an exotic, inspiring story that is suited to the American, Polish or German reader who may not be too familiar with the activities of the Jewish community in Palestine in the 1930s and ‘40s. But in the end, Stern was a marginal episode on the road to a Jewish state, just as Poland was an unimportant country in the diplomatic efforts to establish Israel.

In “Black Earth,” however, for some reason, Poland and Stern take center stage. Snyder explains the connection between the 1938 Anschluss of Austria and 1941’s “Final Solution” with the help of the key term of his thesis: “stateless territory.” He contends that what Hitler learned from the annexation of Austria was that in order to forge the conditions in which annihilation of the Jews would be possible, the state had to be destroyed and transformed into a territory devoid of all symbols of state structure. It could not have an organized governmental bureaucracy, could not conduct foreign relations with other states; its society needed to be fragmentized, which would make possible widespread terror. It starts in Austria and continues in Poland, and there it takes place concurrent to a terror that is spearheaded by the second “state destroyer” – Stalin. It peaks in 1941, when the mass murder of the Jews is begun in the stateless territories that had previously been under the control of the Soviet Union.

In other words, Snyder reverts here to his “Bloodlands” thesis, positing that the murder of the Jews was possible due to conditions created by the Stalinist regime that preceded the Nazi regime. He attempts to apply the principles of this explanation to Western Europe, as well.

At this juncture, however, it turns out that reality doesn’t always fit the theory. How can we explain the dimensions of the annihilation in Holland (approximately 75 percent of all the Jews), which is similar to the figures in Eastern Europe, whereas in France the proportion of Jews that were deported to the East is about 30 percent? France does not fit the category of “stateless territory,” as it was ruled by the Vichy regime, which enjoyed certain authorities. Holland is more like Eastern Europe, as it was dominated by what Snyder terms “state destroyers” – SS officers who were given broad authority. Snyder does not relate to the fact that in Holland, in contradistinction to Poland, there existed a certain political structure, and a council of officials that benefited from administrative authority over various matters.

Local circumstances

It is here that the major problem of the book arises: The formulation of sophisticated definitions and statements falls short of explaining complex historical reality. To understand the Holocaust in Belgium, a country Snyder doesn’t mention at all, it is not enough to refer to the national average of murdered victims (some 40 percent of the Jews were deported, a proportion that is similar to that in France). It is also necessary to examine local conditions there. About 37 percent of Brussels’ Jews were deported for annihilation, while in Antwerp about 65 percent were deported – a number similar to that in Holland and areas of Eastern Europe. In other words, in order to understand the differences, one needs to delve deeper into the complex local circumstances, something that Snyder’s approach fails to accomplish.

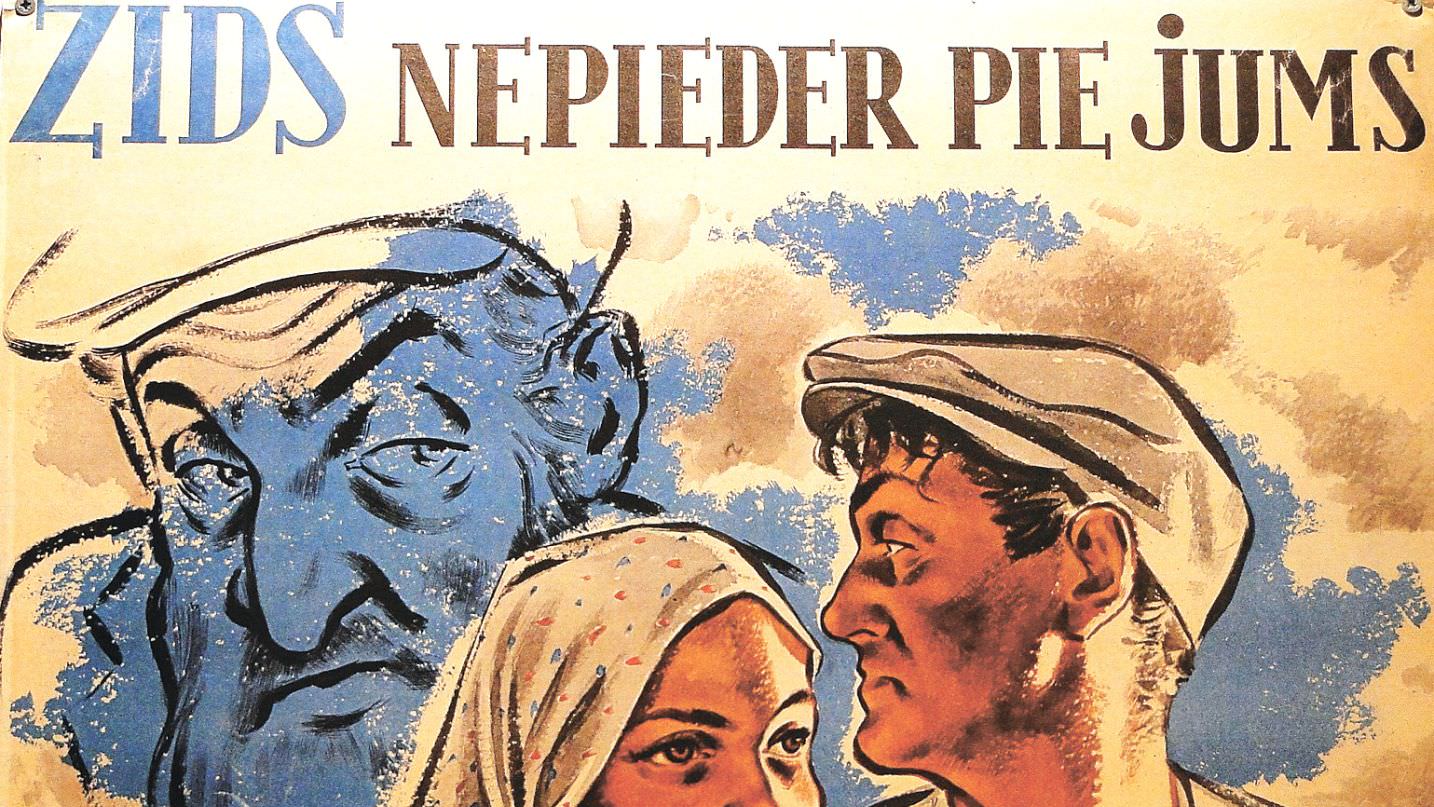

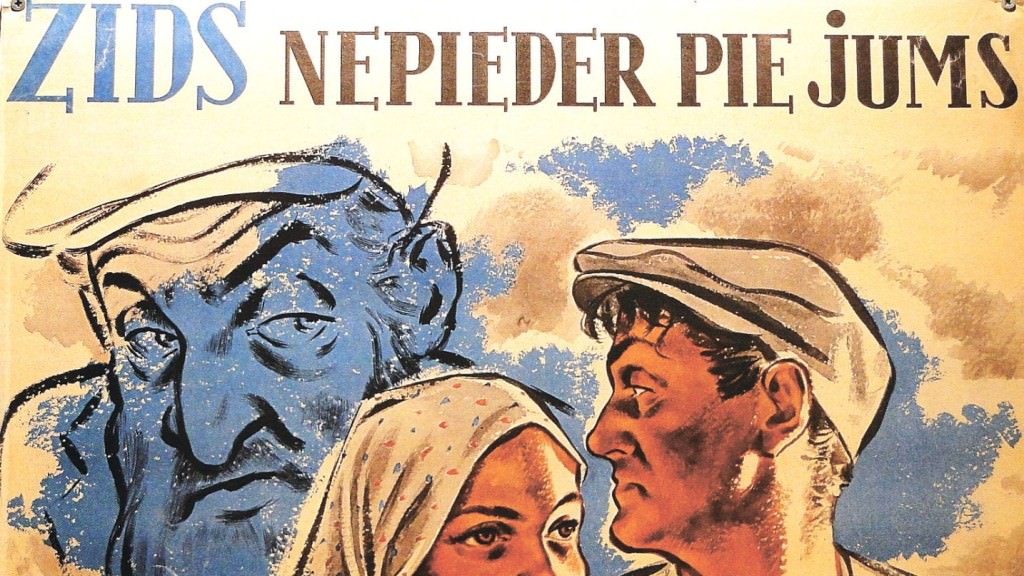

When he analyzes the destruction of the Jews in Eastern Europe, Snyder trods upon much firmer ground. He deals extensively with a point that had evaded him in his previous book: the collaboration of Ukrainians, Poles, Belarusians, Lithuanians, Latvians and Estonians with the Germans in the murder of the Jews. The distinction he makes between peoples whose motivation to collaborate with the Germans partly stemmed from a hope to restore their own independence (Ukrainians, Lithuanians), on the one hand, and others (Belarusians, Poles), on the other hand, is accurate even if not original, as the subject has been exhaustively studied in the past few decades.

However, in his explanation of the savage hostility the various local populations felt toward the Jews, Snyder supplants the term “anti-Semitic” with a term that relates to the Eastern European reality portrayed in “Bloodlands”: Judeo-Bolshevism. The Jews were viewed, most certainly in a disproportionate manner, as collaborators with the Soviets, and thus, as enemies of the nation. This explanation was not originally conceived by Snyder, of course, but it is worth paying attention to. In recent years, some Holocaust and genocide scholars have already rejected the customary and traditional explanation – the existence of historic anti-Semitism – as the basis and exclusive reason for the circumstances that led to the murder of the Jews in a local and very specific context. This is an interesting and thought-provoking development, and Snyder contributes important insights to it.

Conversely, there is an incomprehensible obfuscation that the author perpetrates in his use of the terms “Holocaust” and “Final Solution” (he only uses the term “Holocaust” and not Shoah – which is currently used by quite a few non-Israeli scholars). Snyder does not expressly define it, but it seems that for him, “Holocaust” encompasses the broad context of what occurred at the death camps of Eastern Europe. It includes the annihilation and the brutality toward the Jews, which both the Nazis and the local population exhibited. The reader gets the impression that “Final Solution” relates to the Nazi annihilation policy vis-a-vis Jews, or in other words, the bureaucratic-administrative procedure adopted by that movement in 1941.

In this respect, Snyder follows suit with several genocide researchers who are moving in the same direction, and differentiates between the broad event – which can include varying aspects of persecution and violence but not genocide – and that which can be defined as genocide. The traditional historiography of the Holocaust, and primarily the Israeli strain, rejects these distinctions. It views the Holocaust as a wide-ranging event that contains the years prior to the annihilation, the years of the annihilation, and additional elements that concern life of the Jews under Nazi occupation, the Jewish resistance and even the first few years that followed liberation. Snyder does not deal with this at all.

The concluding chapter of “Black Earth,” it should be said, is quite embarrassing. It is called “Our World.” Hitler, the author contends, was the first global-ecological revolutionary, but his “legacy” places our existence at risk to this very day. At this point, the author shifts his focus from Babi Yar and Auschwitz to the ecological dangers posed today by China and the United States, to food and hunger concerns in Africa, and to another “state destroyer,” Putin, who employs methods toward Ukraine the likes of which characterized the 1930s-era leader in the Kremlin.

About two months ago, Snyder told an interviewer for the French newspaper Le Monde that the next genocide would be a genocide of hunger triggered by an ecological crisis. Is this a warning sign posted by the Holocaust? If it were possible to draw any lessons from the mass murder of human beings, I would propose others (for instance, the need for tolerance, respect for minority rights, a struggle against racism).

When I finished reading the book, I asked myself who might benefit from it. Much of it is highly readable (Snyder is a superb writer); it is fascinating, and is interspersed with heartrending human stories alongside political and social analyses presented in a vernacular that is suitable for everyone. This is a perfect scenario for an outstanding book. But historians will learn nothing new from it, and some have already voiced their strident criticism of it. With respect to the public at large, perhaps it will be better received. But the picture that Snyder paints is a superficial one and replete with erroneous assumptions. This need not, of course, prevent the book from becoming a best seller, which teaches us that at least for its author it can bring prodigious benefit.

By Daniel Blatman

Original article published HERE.